QPP 37: Justin Fenton, We Own This City, on the GTTF

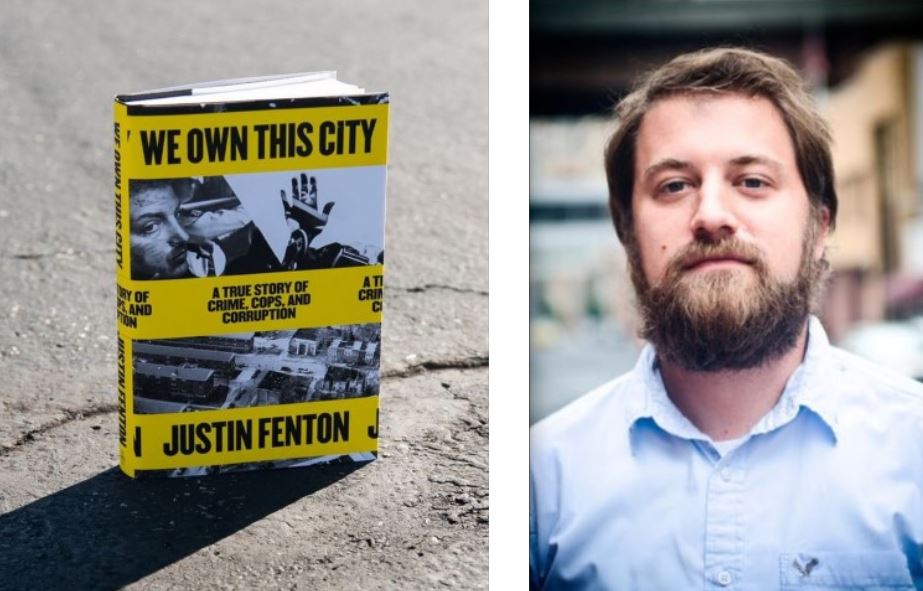

Justin Fenton is a Baltimore Sun reporter and the author of “We Own This City,” about Baltimore’s Gun Trace Task Force.

Episode:

https://www.spreaker.com/episode/43939796

You can also watch this episode on youtube! (I’ve never been certain why people would want to, but knock yourself out.)

Transcript:

[00:00:04] Hello and welcome to Quality Policing. I am Peter Moskos and I’m thrilled to be back and making a podcast episode. I know it’s been a while, but if you’re listening to this and you’re unaware, you may want to go to quality of policing dotcom, because in the past few months I was working on putting together what I’m calling the violence reduction project. And it is it is in response to the increase in murders last year in America, the largest increase in American history by far. And I asked 30 people for their answers, for their solutions as to what we can do to bring down violence now. And it is a collection of about 30 essays directly related to violence reduction. So do you feel free to check that out?

[00:00:55] Again, it is that quality policing that come I am here today, and I’m very thrilled to be here today with Justin Fenton.

[00:01:07] Justin is a crime reporter for The Baltimore Sun and he was part of the Pulitzer Prize finalist staff recognized for their coverage of the Baltimore riots that followed the death of Freddie Gray. And he has recently published his first book. It is called We Own This City A True Story of Crime, Cops and Corruption and an American City.

[00:01:29] It was published by Random House. And in this case, the American city is a Baltimore, Maryland. And I. Picked up the book a week ago, which is just out, and I read it pretty much nonstop, it is a page turner and two and a half days later, I put it down and said, damn, that was a good book.

[00:01:54] And I’m not just saying that.

[00:01:57] And you’ve also done good reporting for The Baltimore Sun.

[00:02:00] And I’m not just saying that because I think, you know, that I can be very critical of journalists when appropriate. But I’ve tended to be pretty supportive of your work because because you do good work and you follow in the footsteps of some fabulous journalists, you follow in the footsteps of Peter Herman, who’s now with The Washington Post. And he was mentored presumably a bit under David Simon of wire fame. And I presume that David Simon himself was mentored personally by H.L. Mencken.

[00:02:27] But I’m not quite certain about that. But it is interesting that The Baltimore Sun has such a storied history on particularly the crime and police beat. And you’ve also and you’ve been there for when did you start there? You’ve been there for a long time. Yeah, I’ve been there since 2005. Is there anything particular about the son or why do the crime reporters last so long? So usually there’s a lot more turnover.

[00:02:56] Yeah, I mean, that’s a good question. I mean, I still feel like I’m learning every day. I mean, the way, you know, the issues, you know, the perspective on things is something that I feel like I’m you know, the landscape is always changing the way a lot of turnover with our police chiefs and an administration. But, you know, I still feel like I’m starting to hit my stride with being able to tell better stories because of knowing more people and having more context and having a better understanding of things.

[00:03:27] So when so you’ve been at this for well over a decade. When did you first get the hint of the corruption that Thatcher later became? We own the city.

[00:03:41] Yeah, unfortunately, the way misconduct was often presented was that it was bad apples and that was easy to go with because it was always isolated incidents. And in terms of like an individual officer being charged with improperly accessing a database and feeding information to a drug dealer and individual officer, dealing drugs from the police station parking lot and working with drug dealers, an officer who failed an integrity saying, you know, so you always had like and then like the King and Murray case in the mid miraz, you know, that was two officers working in tandem. So, you know, while there were certainly lots of allegations of misconduct, the idea that it could be like orchestrated and carried out by an entire squad or that, you know, like it was it was easy for officials to characterize it as as bad apples. And so this case kind of, you know, ripped off the covers in a way that exposed that officers who were so inclined to do this stuff were able to operate in this fashion, you know, for a for a long period of time and in concert with each other. So, yeah, it was years of sort of seeing it emerge piecemeal. And then, you know, the indictment here in the wiretaps and then the officers cooperating with the feds, it just it offered a brand new insight into it in a way that in the past was maybe only whispered about her allegations that couldn’t be supported.

[00:05:10] And so I worked as a Baltimore City police officer from late 99 to mid 2001 and wrote a book called Cop in the Hood about policing in Baltimore in the Eastern District.

[00:05:22] In that book, and I’m paraphrasing myself, I wrote something like, undoubtedly there are corrupt officers because they get caught. But the culture of policing in Baltimore is basically clean and hasn’t aged well 20 years later, that line.

[00:05:43] Do you think the police department changed or was I just clueless to what was going on around me?

[00:05:50] I mean, that’s tough because, again, in the course of researching the book, you know, sort of reconnecting with contacts I’ve had over the years or meeting new people and trying to get them to explain to me, OK, you know, now that it’s out there, let’s talk about it. I grant people anonymity. I would say, listen, you got nothing to lose here. It’s just you and me over a beer. Let’s let’s let’s get real. And like everybody would say, no, honestly, we don’t know about this stuff. And they have their selfish reasons for people to say that for sure. I mean, even if I created someone in Anemone, they’re not going to be keen on admitting to witnessing crimes or taking part in crimes. But people would say, we don’t know what this is about. This is not something that we saw go on. Conversely, the officers got in trouble, say everybody’s doing it. Know Detective Gondo says everybody did this. Morris Ward said you had to do it to fit in. You know, so it’s like, you know, I wonder if both can be true. I wonder if in certain circles or certain units or certain type of work, it was commonplace and it was, I would guess, more casual, you know, skimming some money, not these big heists that ended up being part of what what Jenkins was charged with and pleaded guilty to. But, you know, skimming money, cutting corners, I think that stuff did become commonplace. It was easy to lie about before body cameras especially. But that doesn’t mean that the officers that you saw out there in patrol and other units came in contact with some other units weren’t weren’t doing things right. I think it’s one of the things they try to portray in the book is that it’s complicated. I think that after the trial, everybody did come away with the idea of everybody doing this, you know, lock up the whole police department. And it’s like as you get into some of the characters and stories, you know, there’s people who can credibly say, I didn’t know that was going on.

[00:07:36] And I can. I do. I mean, I don’t think this was going on when I was there.

[00:07:40] I mean, I’m pretty sure it wasn’t hasn’t been caught. My partly it is hard to retire as a dirty cop because it’s a great get out of jail free card for for criminals.

[00:07:49] That’s one reason. The other reason, as I still say, the culture in general doesn’t support that. But I will to sort of add on to what you said, if there it’s very easy to turn a willful eye away from what you think where there’s smoke, because in the police department there is guilt by association.

[00:08:09] There is distrust of the discipline process being arbitrary and somewhat random as to who it chooses to punish.

[00:08:17] Yeah, as if they want to get you. They can because all cops violate some rules all of the time. And that’s not rules or not laws. I mean, I’m talking about petty departmental stuff, but if they want to get you, they can. But certainly, you know, I saw drug squad raid houses and I didn’t like the way they operated. Not that I saw them do anything criminal or dirty, but I just thought they were unnecessarily I don’t know, you know, they didn’t have to cut open that Koch. Yeah, there might have been drugs in there, but come on, you that wasn’t why you cut open that Koch kind of thing. So people tend you know, I talked to officers. No, we don’t want to be part of that mentality, that mindset, which is not to say it was a criminal mindset, but you just turn your turn away from it.

[00:09:06] But I like the one thing you blogged about, something you refer to as the blue cone of silence. And that always resonated with me.

[00:09:13] This idea that you see stuff, you know, you’re not sure about it, or maybe you are sure about it, but you’re not sure it’s going to be handled correctly and you just sort of move away from it and you’re just like, that’s somebody else’s problem. I don’t want to get caught up in this stuff.

[00:09:25] I don’t want to be on the scene when someone files a complaint against that officer. And I don’t know if I’m going to file it, but I don’t want to be there because I have got to cover my own ass. I think I call it the blue wall of ignorance as opposed to silence, because cops do write out cops often. But but you put on blinders so so you can give. So first of all. So you honestly don’t know. That’s that’s the incentive. And the next level also your plausible deniability. But yeah. What’s going to happen if three months later you say, well, we know what happened there at the you know, the corner of of Wolfe and Eager and, you know, three months ago and I don’t even remember like, well, here on the run sheet and says you were there. You’re like, I guess I was. Yeah. A lot of places.

[00:10:07] There’s a character in the book, Ryan Quinn, who he believes that Detective Gondo is dirty but doesn’t have proof. He sees him, you know, having dinner with someone who Gwen is investigated as a drug dealer in the community. And he he doesn’t he just doesn’t feel right. And he sees him interact with people on another occasion and he reports it to the FBI, into the deputy commissioner and nothing happens. And then he’s freaked out that like it’s going to get back to him. And like, he didn’t have the goods, but he went ahead and said something anyway. And it’s just like he sort of regretted it almost. And so, yeah, I mean, I think the thing is a real it’s difficult.

[00:10:41] It’s hard to complain in the same way Spidey senses tingling, and that’s often what it is. Yeah. The NYPD has a. Anonymous phone line, cops can call, by the way, and give tips on other cops and cops use it, as far as I know, Baltimore does not have that. So that perhaps is one way to start. But you also have to have faith in the internal affairs division and believe that they’re on the street on the level when I was there soon after. Before I forget the timeline, though, is the FBI staple’s investigation and on that crashed and burned in part because files were stolen from the Internal Affairs Secret Office, ironically recovered in a Dunkin Donuts dumpster. Then after I left, there was the tow truck scandal. Yeah, and that was the first. It was as scandals go, it was minor in terms of I don’t think anyone was hurt. It was corruption. But I remember talking to a friend of mine who was still on the job and he called me and said, can you can you fathom this? And I said, no. I mean, that was the idea that I could not imagine that happening now, it didn’t help that Baltimore City police went to Puerto Rico to recruit police officers and recruited from one of the most corrupt departments in America because they were later busted by the FBI.

[00:12:09] And some of those dirty cops came to Baltimore and some of them were part of that scandal.

[00:12:13] But that that was like, oh, that was kickback money. That was old fashioned 60s corruption. And that was exactly how I was hung out. Harlan, what’s his name and the stop snitching video. But again, they got outed. They got arrested. And they also said everyone’s doing it. And everyone else said, no, actually, we’re not doing it and you’re criminal. And then in this.

[00:12:34] So maybe because I’m assuming most people listening have not read your book, though they should. And it is We Own This City by Justin Fenton. Effi Antione. It is eminently readable. It’s downright enjoyable. But maybe if you just give a I know it’s hard to do it, quite hard to give a short summary, but what happened?

[00:12:54] Oh, yeah, I’ve I’ve been doing this a few times, you know, so there’s basically a story about a corrupt unit of officers, plainclothes officers.

[00:13:02] For those who don’t know that’s different from undercover officers. These are not people assuming different identities and infiltrating organizations. These are officers who work in plainclothes, unmarked cars. And we’re doing the proactive policing that the agency has relied on for so long and continues in many ways. And they were abusing that power. They were stealing money from people. They were doing searches without probable cause. They were lying on official documents. In some cases, some of the officers were stealing drugs and having them resold on the streets. This was going on for some time. This unit was sort of brought together, though, post Freddie Gray during the time when the Department of Justice was supposedly looking under every rock and behind every corner looking for stuff like this, and they did not find it. And so I sort of trace the rise of Wayne Jenkins, the sergeant and leader of the group, and the officer who was found have been doing the most. And he was viewed within the police department as one of its best. They relied on him to get guns. They thought he was doing a great job. And I track his career with the shifting police strategies, the scandals that arose and were brushed off and sort of how how can all this happen?

[00:14:14] And so it also gets into the death of Detective Sean Suter, who was fatally shot. And there’s a lot of debate about what happened there. And so I try to I try to cover all that at about three hundred pages. So there’s a lot of a lot of material I noticed.

[00:14:31] And maybe it was my imagination. I thought I felt very much the tone of the book change at the end when you shifted the Sean Suiters, Sean Souters death and the investigation. Certainly, as you know, because you reported on it is it’s a. Touchy subject, and a lot of people have strong opinions. I mean, the basic thing is, wasn’t suicide or murder.

[00:14:54] I mean, that’s. The short version of the issue, did you feel any sort of special duty or obligation on how you covered that as compared to the rest of the book?

[00:15:07] Yeah, I think I think I think it’s everything you just said, it is a very sensitive topic. It’s somebodies death and I don’t want to be frivolous with that. I mean, you know, when that when that happened and the connection started to be raised that he was about to testify before the grand jury investigating Jenkins’ and the drug planting incident from 2010, there was a strong reaction in the community that this must have been a murder, that there must have been people in on it. And actually the shift in the story, you know, people within the department started to whisper saying we actually think there’s no evidence pointing to a gunman here. We actually think that he might have done this to himself to make it look like a murder. And that’s that’s a hell of a thing to say.

[00:15:47] I was to say that was certainly my first impression from basically six hours after it happened.

[00:15:54] Well, so, I mean, that’s a big thing. And that’s a that’s a you think about that’s a crazy thing to try to pull off. I mean, you’re out with your partner. It’s dusk. It’s not dark outside the others, potentially people around. That’s that’s a kind of a crazy thing to contemplate, someone thinking they can pull off. And so the officers who I think, you know, you know, command down the investigative level, who brought that forward? We’re kind of I think they were thinking they were saving the community from a manhunt that might lead to someone getting falsely arrested. And instead it became this is a cover up. This is this is this is OK. Oh, come on. You’re telling us he killed himself. And so it’s an interesting it’s an interesting thing where like what what appeared to be what could have potentially been a cover up, which is pursuing somebody who who was actually not not a shooter, morphed into something else. And we’re all left sort of like wondering, well, what’s the real story? And I don’t know that we’ll ever know. One thing I learned from reporting this book is that, you know, ten years can go by before the truth comes out. So this was my best attempt at passing through the available evidence, getting some people to talk about things that haven’t really been talked about and putting more information out there. And ultimately, I think you’ll find that I don’t make a conclusion. I think I think I lean a certain way, but I don’t I make a conclusion because it’s still it’s still pretty controversial and there’s still a lot of stuff that could and we don’t have our opinions, but we don’t know.

[00:17:14] We weren’t there. Really. It’s not clear. Who knows. So, yeah, we can you put I think you do a good job and I’m putting the evidence out there and putting both I mean, presenting both sides and but but anyone who wasn’t there will never know for sure. Probably. And that’s that, that’ll be the you know, that’s how it’s going to come down. I mean, it does Yushan Sudar and I did not I don’t know, I didn’t know him personally, but by all accounts, he was a well, well-loved police officer and human being.

[00:17:41] And I think that also, you know, adds to the tragedy of the situation. Certainly no matter what happened, it’s certainly tragic. Is the process in writing this book, how does that differ from writing stories for the son?

[00:18:03] I mean, you know, writing Search for the Son, especially this topic I.

[00:18:09] We don’t always get to write long and you write long, it’s something you really got to pitch and you’ve got to work it out. And they don’t just take like lengthy multipart stories, although I did do a three part series on this story that was sort of a precursor to the book.

[00:18:23] But you do have to start at like six thousand or something.

[00:18:26] Yeah, I might have been 10 even, but it’s still not pales in comparison. The book, I think, ended up being two hundred thousand one hundred eighty thousand. So, you know, with every story you’ve got, you have to have a hook. You have to have a reason for writing it.

[00:18:40] You can’t say I found more information. I want to write a story. It’s got to be, well, why are we doing it? Why is this timely? Why is it necessary otherwise folding stuff into other stories? And so it’s like I really got to a contextualize everything as I as I explained before, I mean, I got to talk about Marilyn Mosby selection and I got to talk about zero tolerance and I got to talk about how I got to intersect different dates. You know, it was fascinating to me to put one of the first things they did was to make a timeline. I wanted to know on the day they robbed this guy what else was going on in the city. Why might no one have been paying attention to that? It was fascinating to look at the intersections one day. You know, there was a big verdict. And then one of the pretty great officers trials and all eyes are on the courthouse in downtown and Freddie Gray’s all over the front page. And it’s like they’re off doing whatever because no one’s paying attention. The day the civil rights investigation came out saying that officers disproportionately stopped black people and abuse traffic stops the hit the streets, jacking people up, it’s pulling people over for seatbelt violations on gas station parking lots. I mean, like the disconnect between sort of what the people at the top and the official officials want to see happen in our saying is happening and actually how it plays out on the streets eight, nine rungs down from them. That was that was just an amazing thing. And I got to bear down on certain things that I think had I continuing to do daily journalism and I am a daily I’m not an investigative reporter who gets to take a year at a time to work on something. I’m in the trenches reporting every day. I got the bear down for for a little bit of time and say this.

[00:20:13] I really need to get this piece of information. This is extremely important to me. I will not relent on you until I get this. Whereas let’s be honest, the daily journalism, sometimes, you know, you’ve done that story and you’ve got to move on. So it was a I really enjoyed the process. I never thought I never saw myself writing a book. There’s not a an ultimate goal of mine, but I enjoyed being able to tell this story in a more complete way.

[00:20:36] And, you know, I always say I enjoy having written I wish I enjoyed the process of writing more. I’d probably be a more prolific writer if I actually enjoyed it. I find it’s it’s hard, hard work. It’s painful to me to a certain extent. But anyway, I think I, I do it because it’s partly my job and I like to think I’m half decent at it, but I don’t think it’s fun. For outsiders, and I’m reading between the lines of what you just said, what? Of course, every city is unique. We all know that, but the cities also have a lot in common in America. What don’t people get about Baltimore who haven’t who don’t live there, who haven’t lived there, who haven’t been there?

[00:21:23] And I mean, you know, I mean, I, of course, always say crab cakes, but no, not crab cakes. But in terms of the structure, in terms of the politics.

[00:21:32] Yeah, I mean, that’s a tough question. I mean, my my first thing that comes to mind is sort of the battle with crime has just been such an important thing for mayors and police commissioners and legislators and and oftentimes. You know, I think there are. Be careful how I say this, because it’s complicated, I think there are good there are bad things happening with good intentions. I think that these efforts to get guns and to pursue drug dealers are rooted in this idea that people are asking them to get the crime rate down. And yet I think that that manifests itself in ways that the community doesn’t like and doesn’t endorse. And yet it’s there when something’s going on, you call nine one one. I think that I feel like you’ve talked about this, but like corner clearing and stuff like that, like the officers get a call to 911 one from someone on that block saying, get these guys off my corner. I don’t like what’s going on there. And then the officer rolls up and it’s like. You know what? Why are the police hassling us and if there’s this there’s this complicated relationship between the community and the police and I think we’re like we’re it’s not that’s not a new thought. This has been going on for decades, but I feel like we are. Thinking about it differently, you’re starting to or wrestling with what is proactive policing mean, how can it co-exist without harassment? And so it’s about Baltimore that’s I try to intersperse that throughout the book that like, you know, they’re doing zero tolerance while witnesses are getting killed in a home, is getting firebombed that kills an entire family and five children.

[00:23:17] You know, there’s no way I’d quit a couple of months before that, but I probably would have handled that. Call it. I still been there.

[00:23:23] Well, OK. Yeah, I mean I mean, you know, there’s this you know, they’re doing these things trying to get down crime. And and then there’s this constant turnover again. When you can’t get crime down, you get you get food ID, you get run out of town and then someone else comes over and they don’t know what they’re doing and they’re trying to learn the city. And it’s it’s one crisis to the next, honestly, that, you know, there’s there’s some there’s such a lack of reflection because there’s always something else going on. So they’ll do studies and reports. And then, you know, six months from now, the Koch command staff is turned over. It’s not the same people who commission that reporter who even read that report. I just think it’s a tough it’s a tough environment and a lot of it comes down to leadership.

[00:24:04] But that kind of avoids the issue of what about it? But you have that leadership has consequences. And I think Baltimore is more than its fair share of bad leadership, to be honest. And I I did get the sense when I lived there, it was the city of crisis to crisis something this week. And then, you know, tomorrow a water main breaks and then a train derails.

[00:24:24] And it’s just it’s sort of every city isn’t like that, quite frankly. But so to give a sort of a bit of a which is now historical background, but so arrests maxed out at above one hundred thousand a year and I believe 2003. That’s off the top of my head somewhere around there. You think it was one hundred and fourteen thousand, but I could be wrong. After 2003, arrests declined consistently.

[00:25:01] Pretty much every year, murder declined use of force. I believe police use of force declined and murders went from, you know. Above 300 to under 200. Everything was getting better, was my sense, not that it was perfect, not that there weren’t flaws, but for literally 15 years, everything was trending in the right direction and the population of Baltimore actually briefly increased for the first time in 50 years. And I remember going there in 2014 and saying, you know, for the first time since I’ve ever been in this city, it looks better, partly because of immigrants have moved into my old neighborhood of Highlandtown and Greektown and crime was down and, you know, from results are building or artists living in it. And, you know, and fewer people were being shot. And I felt that that progress was. Willfully denied. And I don’t quite understand why, but this idea of blaming Martin O’Malley for encouraging an arrest based zero tolerance philosophy, when I was there for something that happened 15 years later, I just thought was disingenuous at best. Things got worse, significantly worse after Freddie Gray. In some ways, Baltimore was, I think, saw the increase in crime that the rest of the country just saw last year. But there was, at least partly by design and partly by low morale and drug corners were no longer cleared, partly because of the DOJ input.

[00:26:43] And I will say till my dying day, they can be cleared legally and constitutionally, and they must be for the sake of the residents who live there. But that’s not happening anymore. The fact that the DOJ came in, it was a pretty shoddy report and made some very good points about how the department was dysfunctional at times. But there were just some basic I don’t know, their methodology wasn’t clear. It wasn’t clear who wrote it. And the largest corruption scandal in Baltimore history was brewing under their nose. And they were clueless because I just think they were clueless. It doesn’t surprise me. They didn’t know. But I think it’s revealing that you have a consent decree that I still don’t know what it’s accomplished and it’s only really now starting to be implemented.

[00:27:23] I mean, you know, it’s been in place for four years, and yet they say they’re only now they’ve been rewriting the policies, have been studying things and are only now starting to implement the training. So I think we’re at a turning point now. But, yeah, it’s been it’s been six years to get to this point.

[00:27:37] You know, we’ll see in two years from now, like whether it’s a turning point. I also gather there might be. But I mean, murders are higher than they ever are and the population is declining again, in large part because of crime. People don’t for good reason, don’t want to live in neighborhoods where gunshots are a daily occurrence. And you got Fox trot, the helicopter buzzing above you.

[00:27:55] There are lots of issues going on. So one thing, corruption, not just in Baltimore, but when there are large scandals in policing and Rampart in L.A. comes always jumps to mind. Yeah. They always have certain things in common, which is highly decorated officers with a lot of arrests and gun arrests, there’s always drugs involved, sometimes some prostitution thrown in for good measure. And they’re always a specialized plainclothes unit and they’re always geographically separated, segregated from the rest of the department. That doesn’t, I’m sure, their units where you get all that that aren’t corrupt and I just don’t hear about them. But every time there’s a big corruption scandal, you always have those similarities to me. If I had ever risen above the rank of rookie patrol officer on the midnight shift, I would say this is where supervision and leadership comes in.

[00:28:53] I guess to put it into question is who do you blame for this? Let’s say we’re going to blame the individual officers. No, in parts of the book made me angry when they read everyone’s doing it. No, that’s just not true. You and all your criminal friends were doing it. That’s not everybody. But a lot of.

[00:29:09] But but still, you know, a half dozen plus bad cops set the police department back. I don’t know who years at least. How do you at some point, leadership should have stopped this and you talk about some of those leaders and analysts, I should also mention noting that one of the guys who was in prison, I went to the police academy with many of the names of the book. I know from my from my time there. So some of these people I know personally, how can you prevent this? How could it have been prevented? And also, let me throw in another side question. Do you think the police department is doing anything to prevent this from happening again?

[00:29:50] You’ve covered a lot of ground in that wind up. Let me let me try to take it one by one. I mean, first of all, you know, I think it’s not O’Malley’s fault. I mean, I think that the zero tolerance was a you know, it’s not surprising that he tried to import New York police commanders, New York policing styles to try to duplicate the New York crime declines. It just wasn’t. The New York turnaround is there’s much more going on there than just, you know, higher numbers of arrests. And I feel like here that that’s how it was implemented. And so they went from locking people up. To put a chill in the community that you better you better keep yourself. You better not do anything wrong because we’re going to lock you up for anything to then the Bealefeld years was sort of like, well, let’s try to be more precise. Let’s try to highlight geographic zones better. Let’s try to highlight individuals better and let’s try to be more precise. And they had a working relationship with the prosecutor’s office where they were in lock step with each other. And I think now I think that that all of that throughout that time period, there was aggressive policing encouraged in good ways. You know, do I think that Anthony Barksdale, the deputy during that time, you know, wanting people to go out and do certain things like absolutely not. He’s such a great person to talk to because he understands he’s able to talk about the reasons why police do the things they do and the things you want them to do and the goals during that period, even if maybe on the lower levels, it didn’t get carried out the way he wanted to or things were being kept from them. And that’s a pretty favorable take on him. I think there are some people who say that he did encourage a loose climate in terms of this kind of stuff.

[00:31:46] But do you hear him talk about it is pretty inspiring, I would say. But I think, you know, you see Jenkins moving from making three hundred arrests a year during zero tolerance. And he personally, you can look it up. You know, he personally made a ton of arrests during zero tolerance.

[00:32:02] And then you see him moving into the violent crimes impact section, which is the main tool during the the Barksdale years after you for one second, just because people tend to assume cops make more arrests than they actually do where a cop was on the street, you know, make between probably 10 and 20 arrests in a year, I mean, assist in many more. But it’s not cops generally don’t arrest somebody every day. So the three hundred arrests is mind blowing.

[00:32:36] That’s just the ones that ended up in case that’s not the ones that were being rejected at central booking. So, yeah. And then you see him in these aggressive plainclothes units and they’re doing aggressive work. I mean, they’re going after big players and there’s all sorts of allegations that are coming forward that time about them sort of doing a search without a warrant. They call them like sneak and peek, still finding something and moving it or, you know, misrepresenting how things went down in order to get into places. And and it’s always. You know, the there was a remarkable instances where defendants in a federal court would say it would stand up and say or take the stand and say, I did what I did have drugs, but they’re not telling the truth about how that happened. That’s the kind of stuff is remarkable to me. I mean, I don’t I don’t see stuff like that play out very often. And that’s that was happening during this time. And yet people were saying, yeah, give me a break, man. You know who’s going to believe you? There’s a remarkable line where a judge says, well, if I believe you, then I have to believe all these officers are lying. And it’s like officers who are in jail for lying. So so its terms of accountability. I mean, I think that. I think I like to blame everybody. I mean, there’s some defense attorneys will tell you we knew all about this and yet people weren’t saying it to me. They had their own reasons for protecting their clients interests. They would say, you know, that’s not worth it. We shouldn’t bring that up. No one’s going to believe you. Let’s try this other angle. Why don’t you just take a plea, you know, and there’s reasons for that. There’s prosecutors who want to win a case and they’re brushing off concerns when they do come forward. And defense attorneys are saying, give me a break. They trust the officers. They they believe them. They’ve worked with them over the years. They’ve seen them. Jenkins, one prosecutor told me that Dinkins would call in the middle of the night asking about how to go about something the right way. And so why would she ever think that he’s not doing things the right way? Then you’ve got to talk about the supervisors. Dinkins became a supervisor, and that’s difficult. He’s supposed to be the one providing that check on his officers. He’s the one on the ground with them. He’s the one. In the houses with them, he’s driving around with them and then he reports back to the lieutenant who’s got three other sergeants in his squad and checking in with them, expecting them to give reliable information. It really does emphasize the importance of sergeants, the white shirts, the commanders, they get all the you know, they’re in all the meetings and the briefings and they’re the ones who get. But but it’s those people. It’s those frontline sergeants. They have such a crucial role. And in this case, we had three sergeants who are in prison now for for doing things. And so it’s like, you know. There’s that there’s a lot of blame to go around.

[00:35:23] Judges, you know, I could go on and on, but on a more personal level, on reporting, on doing your job, how do you deal with the trauma of what you see?

[00:35:36] You know, I often say that I don’t experience it in the same way that the officers and the people in the community do, I mean, I show up after the fact a lot of the time and now having to cycle through all this kind of stuff, the subject matter and talk to people experiencing it every day is certainly a challenge. But we we have a different role to play.

[00:35:59] Certainly, I was embedded with the homicide unit in twenty fifteen, and that’s one of the first times I think of is the first time I think I ever sort of stood over a dead body, multiple dead bodies. And that was it’s amazing to me that people do that for a living every day or just even the medical examiners, people in the health care field.

[00:36:20] I mean, it’s yeah, it’s something. But but I always say that I’m motivated. I’m I’m surprised I’m not burned out yet. And the reason I don’t think I’m burnt out is because every day there’s this new story that has to be told. And I don’t this is not like a you know, it sounds sappy, I guess, but, you know, every day it’s like, oh, gosh, if we don’t tell the story, it’s not going to get told. Let’s let’s let’s get to work. And that’s the way we approach it. And you don’t have enough time to really reflect on it. I remember in twenty fifteen, feeling very emotionally drained, just having everything going on city that crime spike that occurred was, was really shocking. You know, just like you said we were below two hundred homicides and even though it didn’t we didn’t get there again, we weren’t, we weren’t far. And it was like oh my gosh, oh my gosh. Like when it went up overnight, like 80 percent higher. And it’s still there. It’s been there every year. And yes, like you said, every other city is now experiencing that, too. And you look at what’s happening in like Philadelphia and other places. I mean, it’s staggering and it’s hard not to make some of the connections you’re making about the way, you know, things, that things have shifted and and what we see. And yet, I think people are are right in a lot of ways to to say that we want to we want a different kind of policing. And I wonder if that means this is our new normal. If people do want officers to back off and have a different role and that presently is leading to the crime spike we’re seeing. Is this the way it is? And that’s a that’s a troubling question. But I know that’s something that you think about a lot to add.

[00:37:58] Another twist to that I think is particularly troubling because I think a lot of the voices are coming from outside of the community. And if you live in a high crime community and want less policing, we should listen to that voice. I don’t live there, but I hear a lot of outsiders in the name of racial justice, a lot of white outsiders saying that black neighborhoods need less policing.

[00:38:20] And that’s an interesting point. I remember there was I was waiting for this. There was a Gallup poll that came out months ago that found that black Americans did not want to defund or lower police funding by a margin of like 70 percent. And I was like, you know, there’s a there’s there’s folks who we’re not hearing from in this conversation. And I think our current leadership gets that. I think the mayor of Baltimore right now is from the community, families in the community who grew up in the community. And I don’t think he I think he’s trying to thread that needle. I think he wants to reduce it where it where it can be reduced or where it can be made better. And but I do not think he is in abolish or defund the police guy. I just don’t see that coming from him. I do think he’s going to try to make some inroads on it, though, in a way that’s hopefully positive.

[00:39:07] Well, the other polling that he referred to polling has consistently shown that black Americans want more policing more than white Americans do. And just because black Americans are more likely to live in neighborhoods with crime is a greater issue now. More policing and better policing are not mutually exclusive. And I don’t mean you like the police to say you want more of them. And the onus is on the police department to provide better policing. But this idea that we’re going to get better policing with less money is to me, absurd. But in some ways, I think Baltimore has an advantage in having a black political power base and being a black majority city. It avoid some of these debates that Seattle and Portland in Minneapolis and New York are having.

[00:39:49] And I think just to just to build on that one, one reason why, though, I mean, some might say that the reason they support police very much is, again, because there is not a there hasn’t been another apparatus like the like the alternative isn’t hasn’t been presented or formed.

[00:40:06] And so it’s like well presented with the option of taking the police out of my neighborhood where the shootings. Of course not. But but perhaps maybe if that was presented in tandem with another alternative, I’d be curious to see the results.

[00:40:20] But if this were an academic experiment, I would not get approved by the Human Subjects Committee. I am all for alternatives, but the idea that they have that they’re balanced against policing to me is absurd. We will know a. Lately, when demand for police goes down because people will stop calling for police, let us get there. It doesn’t have to come from the police department budget, which is tends to be less than a lot of people think. It’s usually three to six percent of state and local funding goes to law enforcement. That leaves ninety five percent of the budget or higher taxes. We don’t need to be on police to set up alternative structures because I’m skeptical of those structures. I’m not saying they couldn’t work, but I want them to work before we start getting rid of police. And that’s, I think, sort of a missing step.

[00:41:07] Baltimore also, in my mind, positively isn’t kind of immune from the defund movement because the judge who’s running the consent decree simply said, sorry, but you can’t defund.

[00:41:19] It’s not I mean, isn’t that isn’t that amazing? I mean, honestly, there’s this there’s this conversation and this push.

[00:41:24] And yet our reform efforts that were already undertaken before that kind of went mainstream, quote unquote, you know, was saying like, no, you’re locked into a process here where you will be spending more money on police, more technology, more training, more officers. You know, if you’re community policing plan involves officers spending, I don’t know, 40 percent of their time interacting.

[00:41:44] And there was a community in a positive way. You need more officers so that people can respond to calls while these other guys are guys and girls are talking to people and just making making connections in the community. So, yeah, it’s a it’s a really amazing sort of confluence of events.

[00:42:03] Are you familiar with them, Alex Kotlowitz, his book, the title An American Summer Love and Death in Chicago.

[00:42:11] I’m familiar with the author, but he’s a great author.

[00:42:14] But he talks very much about the trauma of violence, both at a personal level from writing the book, but also to simply the victims of violence. I think often that is not the idea that, you know, it’s so easy to read about. A shooting in the paper are often not read about a shooting in the paper and not understand how that the trauma of that the to the victim, to the loved ones, to the family, it’s it’s just decimating to to life around that, that, that. And I mean, it’s part of the reason I care about these matters is because I’ve seen some of that trauma and my God is a brutal and of course, you have the police officers, the the EMS people, the doctors, the nurses that have to deal with, too, at some you know, some people deal with it better than others. And actually, personally, I don’t think I had a problem with seeing death and Gore, but it’s a heavy ask to say this is part of your you know, we you know, we are asking it and we have to hold everyone accountable for their behavior. But it’s a heavy ass to say, OK, this you’re going to see a lot of people dead and dying. You’re going to, you know, hear gunshots of you. Occasionally they might be at you and also, you know, treat everyone with respect all the time and also, you know, get people into cops who don’t want to be put into cuffs. Those are all tough ask. But that that is sort of separate from what you’re writing about in your book. And we own the city and get the title out there as much as possible.

[00:43:51] The.

[00:43:55] So it’s been turned and it is being turned into a TV show and not just any TV show, but a TV show by the. Famous David Simon, who wrote Homicide Life on the Street, was a Baltimore Sun reporter and is perhaps most famous for at least in Baltimore for The Wire, though he’s had a bunch of series since then. How did that come about? You just got the magic connection and you’re like, this is going to happen.

[00:44:26] Yeah, I mean, Simon is someone I’ve known over the years.

[00:44:31] And I mean, he remains interested in the things going on in the Baltimore Police Department. He’s written a blog post about the way they change the way homicides were charged, you know, requiring prosecutorial sign off on it. So we’ve been in touch. And during the trial, you know, again, there’s this extraordinary couple of years where we had the Freddie Gray case, we had the unrest, we had the charges, we had the reform. We had to keep it Souter’s death. And, you know, he said, like, I want to make a show out of this. HBO wants to make a show out of this. And you ought to write a book. And, you know, I wasn’t contemplating that at that moment. I was covering the trial. I was filing daily stories.

[00:45:09] And it seemed like it came in part from him. I don’t know.

[00:45:13] Yeah, yeah, yeah. And so it’s been in the works since then, really. And it’s just now, you know, kind of broken through that it’s actually happening. But yeah. So it’s been a great I’m in the writers room, I’m a I’m a consultant and I help them to, you know, they’re looking for real life things that happen. They can be scenes that help tell the story is going to be a six part miniseries. And, you know, I help with keeping it true to life and pursuing things that maybe I didn’t have in my book that they’re interested in building out a scene. And so, yeah, it’s it’s it’s not only Simon, but Ed Burns, who works on The Corner and The Wire and George Pelecanos and sort of got that team back together. So it’s it’s an incredible thing to be a part of. It’s there are sort of I guess it’s there if there’s a trilogy of Baltimore shows this is the third in the trilogy. I’ve never met Ed Burns.

[00:46:08] I do know George Pelecanos not well, but I’ve met him. And actually I’m a big fan of his fiction. He writes he writes crime novels in Washington, DC, and he’s written a bunch of them. And of course, he’s a fellow Greek American. So I was looking for that. I will give you one bit of advice and perhaps in closing, but one of them never do a book signing next to David Simon. I did one once and it was in Sydney, Australia, and it was perhaps the most depressing hour of my life as the crowd lined up around the Sydney Opera House for David Simon and I signed, I believe, zero copies of zero.

[00:46:45] You didn’t even get a little a little extra. No. Give you there was one or two. Any overflow at least.

[00:46:51] I got to talk to David Simon during that. And he was he was very kind to me.

[00:46:55] Yeah. The pandemic is any any traveling I might have been able to do for book promo is sadly been restricted to what you’re seeing right now. I’m happy to be here. I’d like to be there in person and in other places. But this is my what what can you do? It’s it’s a global pandemic.

[00:47:11] Yeah. Thanks very much. This is Peter Moskos, Quality Policing. I’m here with Justin Fenton, who has recently well, he wrote and has recently been released.

[00:47:23] And it is We Own the City, a true story of crime and corruption in an American city. And that American city is other than the American city of Baltimore, Maryland.

[00:47:35] And keep up the good work. OK, nice talking to you.