by L. Garcia, a Chicago Police Officer

Chicago, as they like to say, is a city of neighborhoods. Each with its own issues, history, and identity. I’ve policed a few of them. Chicago is also an incredibly segregated city in terms of race, income, and violence. The posh Magnificent Mile, with high-end boutiques and fancy steakhouses is a sharp contrast to a few mile west or south, Garfield Park or Austin, or Englewood, with vacant lots and open-air drug markets. There is a sense of desperation, disorder, and poverty.

When police officers are assigned to their respective districts, they become part of that neighborhood. Whether they realize it or not, they start to identify with that neighborhood. I grew up in Chicago. I went to public schools. Both my parents are immigrants. When I police a new neighborhood, I become familiar with the average “working Joes and Janes.” I become familiar with who walks their dog and goes to work at the same time each day. I know who their children are.

I also get familiar, to an even greater extent, with who’s standing on the corner selling dope, who is looking to buy, who the local gang members are, who the likely shooters are, and who appears to be looking to rob or steal. Other than the “decent” residents, no one is more familiar with criminals than the police. In fact, sometimes police officers know more than the residents who hide inside out of fear.

Ask the Black and Hispanic residents of high-crime neighborhoods. Police know these people. We care about them. We work for them. We protect them. We are them. Where I police, I don’t see reformers. I hear talk about Black lives from white people who live in very safe neighborhoods, people who not only don’t live where I work, but won’t even risk driving through. These people consider every police interaction with a “person of color” a civil rights violation, but think of hundreds of more Black men shot as just some abstraction, an inevitable consequence of an unjust society.

The police know who the bad guys are. Police need to be allowed to confront them.

In order to address the violence in neighborhoods today, police need to be allowed to police. It means legally clearing corners, apprehending criminals, and using the constitutional strategies and methods necessary to maintain order and reduce violence. Letting us police doesn’t mean absolving us of accountability, nor does it mean allowing police to become the Gestapo. Policing doesn’t mean a police state nor illegal behavior. Policing does mean letting us confront and stop suspected criminals.

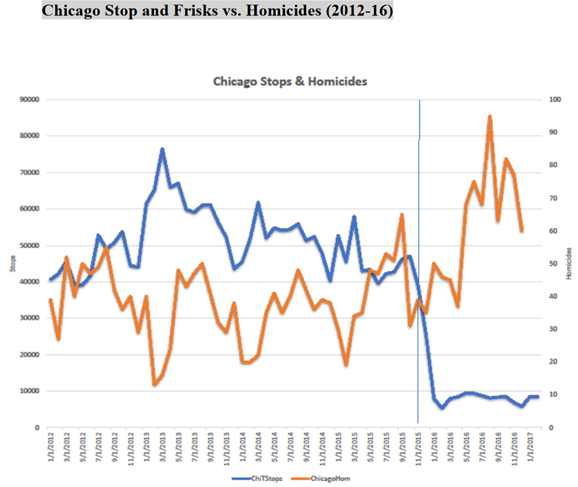

Chicago policing changed, and for the worse, after the Laquan McDonald shooting in October 2014 and the subsequent scandal and cover-up. The City of Chicago reached an agreement with the ACLU that transformed the way investigatory stops were documented. No one wants to be Monday morning quarterbacked by people who have the benefit of 20/20 hindsight. Police morale can and did change overnight. For the men and women of the CPD, this was our Ferguson moment: a high profile incident, a questionable shooting, a very real change in proactive policing.

The greatest change was the effective end of the investigatory stop, known as a “Terry Stop.” Suspected criminals were stopped based on reasonable suspicion and police filled out a “contact card.” Before 2015, these stops happened more than 1,500 times a day. Was every stop needed? No. Did every stop result in a citation or arrest? Of course not. Nor does each stop lead to one less shooting. But collectively, legally stopping people based on reasonable suspicion reduces violence. If there is a better way to reduce violence, I’m all ears. But ending stops increased violence. This is the kind of trade-off — between more aggressive policing and greater public safety on the one hand and the reality that such policing is not without harm —is what we should be honestly discussing.

The police aren’t perfect. Cops are human. Not every stop will be of a criminal suspect. We know this. Innocent people are stopped. But when this saves lives, this is the price that must be paid. Aggressive policing can be and must be both legal and constitutional. But it needs to be done.

The ACLU — an organization with a fondness for lawsuits that has become less about free speech and more ideologically anti-police — was given free reign over CPD policies and procedures concerning investigatory stops. A state law accompanying the agreement expanded the data collected during the course of an investigatory stop. Not only was this new report, the Investigatory Stop Report (ISR), more involved and time consuming, but it also opened new avenues for scrutiny and potential lawsuits against individual police officers.

After the drastic decline in stops in 2016, police stops increased from 2017 through 2019 (though they are still not close to pre-2016 levels). This is in part because the ISR form was shortened. Violence declined in synch. In 2019, there were 519 murders. In 2020, with anti-police protests, looting, and a seemingly strong push for defunding the police, I’m sure investigatory stops declined again. We know murders increased 50%, to 769, the largest increase since 2016.

The ACLU agreement explicitly calls for audits and identification of officers who don’t document stops appropriately or, and this in the ACLU’s opinion, in which cutting a person a break for a bag of weed means he’s “innocent.” Like of formal punishment, be it arrest or citation, does not mean police don’t have legal justification to stop, pat down, or search someone. Active drug dealers and known violent offenders who are stopped, perhaps frisked, and not cited are not, as the ACLU likes to say, “innocent.”

This is the kind of trade-off — between more aggressive policing and greater public safety on the one hand and the reality that such policing is not without harm —is what we should be honestly discussing.

“Reformers” seem to want to both discredit the CPD and also hinder and discourage proactive policing. Sure, it’s easier for police to do less. That’s what many reformers want. For the ACLU, fewer stops was the goal. A feature, not a flaw: “If that number is going down, that’s really good news.” But at what cost? The police know who the bad guys are. We need to be allowed to confront them. Policing saves lives.

Police stops do happen disproportionately to Black and Hispanic men, at least based on the Chicago population, which is 30% Black. But violence is racially disproportionate. 80% of Chicago homicide victims are Black. And despite a declining Black population, the Black percentage of homicide victims and shooters is actually increasing. Any successful attempt to save lives by policing shooters will be racially disproportionate, at least based on the general population, because so are the shooters.

To reduce violence we need a well-trained, supported, proactive police force. The current climate incentivizes inaction by police. In Chicago, specifically, it’s clear that the top prosecutor, Kim Foxx, and the police are not on the same page. Police don’t want to be the next news story. Police might just be in the wrong place at the wrong time, and that might be the next news story. Police believe they can do everything right, but if something is not to the liking of the powers that be, you could be the political pawn losing pay, your job, or your life. There’s a media itching to break the next police “scandal” news story. We won’t get violence reduction by throwing police to the wolves to score political points. Police avoid being the next cause célèbre by being reactive, by avoiding and minimizing risk, by minimizing exposure. This attitude and style of policing costs lives.

Violence reduction can happen overnight, but it requires depoliticizing policing. It requires some guts from police and political leaders. It requires politicians losing their egos. It requires some unpopular decisions at times. It requires letting the crime experts of their respective communities harness that knowledge and applying it. It requires the police administration understanding the beat cop’s perspective. This isn’t an essay advocating the police never be questioned or held accountable. It’s an essay advocating for reasonableness from everyone from the beat officers to management to mayors and political leaders.

Management and leaders need to show some trust in their street cops. We are the ones doing the grunt work. We are the ones with boots on the ground who see and encounter the people responsible for committing atrocities. We are the ones who know first-hand what happens in neighborhoods. We know the unique issues facing these neighborhoods. We know the communities’ concerns. We know who needs to be put away, if only for a few hours. Street cops work these streets eight, ten, twelve, and eighteen hours at a time, sometimes many days in a row.

Upper management can point to all kinds of numbers, patterns, maps, and intelligence, but all of that isn’t possible were it not for the cops who get out of their cars, not just to talk to the good people of the community or dance for some feel-good video, but to confront the men throwing up gang signs, shooting and robbing people, and harassing the working men and women.

Each cop in each respective neighborhood plays a unique role in tampering violence. The cop working in Austin knows Austin. The cop who worked in Englewood knows Englewood. If you’re putting the cop who worked in Austin in Englewood, they might not be as effective immediately, but they can learn. You learn by doing.

We may not be able to arrest our way out of all violence, but we can certainly decrease it. It requires being proactive and going after violent offenders.

The consensus among police is that management and politicians is to have police do less. A very hands-off approach to law enforcement is sometimes implied and sometimes stated explicitly. This means no car chases (and the inherent dangers and benefits of them should be debated), minimal force (which is a good ideal but often fails to acknowledge that force is a necessary part of the job), and a sense of being a political pawn when things go wrong. It’s true that the fewer stops police make, the less risk there is. Less uses of force, fewer complaints, fewer lawsuits, less physical danger. It’s self-preservation. It also isn’t policing.

Police have no problem facing physical danger or running towards gunfire. The police want to give that extra effort to prevents the next shooting victim. This goes beyond simply taking a report or driving in circles all day. We may not be able to arrest our way out of all violence, but we can certainly decrease it. It requires being proactive and going after violent offenders.

Politicians hold the power; the media control the narrative. In the current political climate, thousands of lives will be harmed and lost, especially in our most marginalized communities. Whom do the loudest voice from outside of the community represent? While police must strive to be better informed, better trained, and better prepared — and willing to criticize and hold bad police officers accountable — the police need to be supported when they have done their job correctly, even when it looks ugly. If the public wants an explanation, that’s fine. Leaders need to explain what happened, yes, objectively and from the police perspective. Small things like that go a long way towards incentivizing a proactive police force.

All police want is support when a job is well done. Support in the form of true, beneficial in-service training. Support in the form of resources. Support in the form of standing by police when something goes wrong, as will inevitably happen, even when the job was done right. Police aren’t punching bags. Police want to get the bad guys. Police want to keep their communities safe. We know how to do it. We’ve done it before. We need to be permitted to do it again.

_____

L. Garcia (a pseudonym) is a born and raised Chicagoan who has been a Chicago Police Officer for more than 5 years. They attended University of Illinois at Chicago and earned a master’s degree from DePaul University. They worked as a beat cop, area wide, and citywide units targeting gangs, guns and other violent crime. Garcia currently works on the West Side of Chicago.

The views and opinions expressed here are the author’s own and do not reflect those of the Chicago Police Department or the City of Chicago.