by Richard B. Rosenfeld and David A. Klinger, professors at the University of Missouri, St. Louis

Many American cities have experienced a precipitous increase in homicides and gun assaults during the summer and fall of 2020. It will not be easy to stem the increase in violent crime, but three elements should be part of any successful anti-violence strategy: Subduing the COVID-19 pandemic, redoubling smart policing tactics, and implementing police reform.

Violence Spike

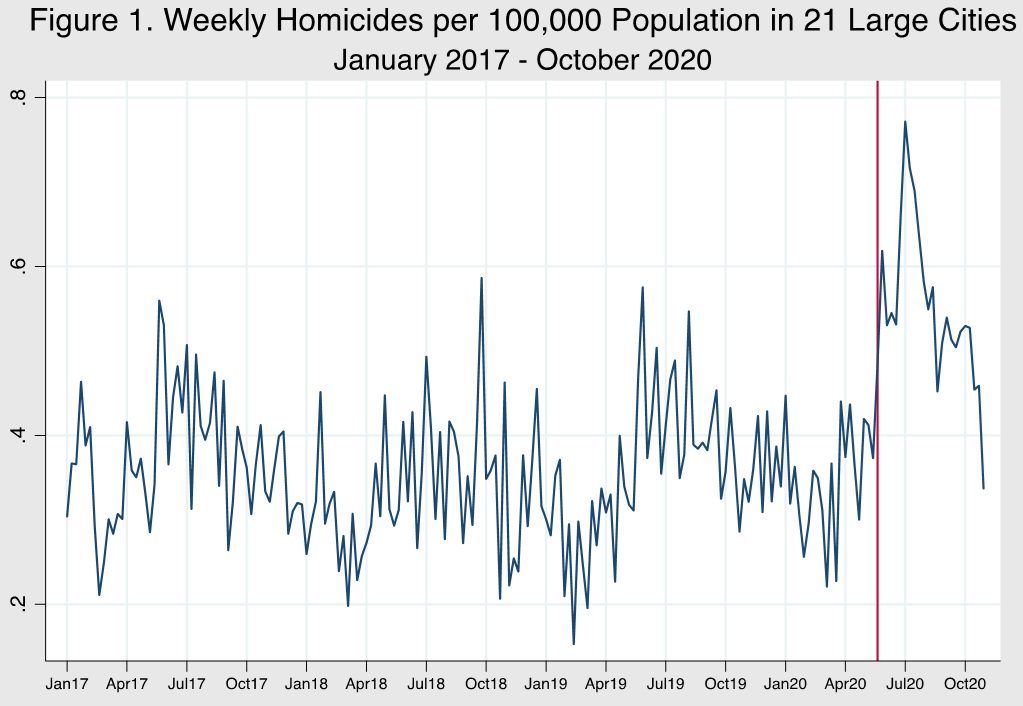

Violent crime rates in cities large and small skyrocketed during the past several months. An example of this is shown in Figure 1, which displays the average weekly homicide rate in 21 big cities between January 2017 and October 2020.

The weekly homicide rate exhibited a rough cyclical pattern with no clear upward trend until early June of 2020, as denoted by the vertical red line in the figure, which indicates a statistically significant increase in the homicide rate for the 21 cities examined. From June to August of 2020, the homicide rate was 42% higher than during the same period in 2019. In September and October, it was 34% higher than the year before. There were 610 more homicides in these 21 cities during the summer and early fall of 2020 than during the same period in 2019. Assaults committed with a firearm were up 16% in the summer and early fall from the previous year (see Rosenfeld and Lopez, 2020, for more information).

The rise in violent crime was strikingly abrupt. It began during the first days of June, when nationwide mass protests emerged in the immediate wake of George Floyd’s death during an interaction with four Minneapolis police officers. The convergence in time between the protests and the uptick in violence is probably not coincidental and is not unprecedented. We saw the same combination of social unrest and increased homicide five years ago after controversial police killings in Ferguson, Chicago, New York, and elsewhere (Rosenfeld, Gaston, Spivak, and Irazola 2017). Crime rates also rose in the aftermath of the urban riots of the 1960s, many of which were sparked by contentious police-citizen encounters (National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders 1968).

Deploying all available personnel, including those currently assigned to specialized units or who work desk jobs, to targeted patrols in violent hot spots would be a wise way to proceed.

The connection between social unrest, especially that triggered by perceived police misconduct, and increases in street crime is a longstanding social fact. The nature of that connection remains somewhat uncertain, although it likely involves diminished institutional legitimacy (LaFree 1999). And any assessment of the recent spike in violence must take into account a social fact that has not been present in previous instances of unrest linked to perceived police misconduct: the social disruptions caused by the arrival of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the United States.

Whatever the source(s) of the current increase in violence, the situation on the ground suggests that efforts to turn the tide should, at a minimum, include attention to subduing the COVID-19 pandemic, strengthening policing initiatives that have been shown to reduce crime under normal circumstances, and implementing police reforms to improve police-community relations.

Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to police practices that diminish the capacity of law enforcement agencies to engage in the kinds of smart policing that can help to keep crime in check (see below). Agency directives to maintain social distance and limit officer discretion have reduced police presence and self-initiated activity, including making arrests and engaging in community policing efforts (Lum, Maupin, and Stoltz 2020). Bringing the pandemic under control and restoring police activity to adequate levels obviously will not happen tomorrow (and probably not before the widespread dissemination of effective vaccines). But the urgency of the current increase in violent crime requires immediate action, and we can think of no better response than to redouble efforts at smart policing.

Smart Policing

The term “smart policing” has multiple meanings in current policing research and practice. In all of its applications, however, smart policing entails the use of data and intelligence to inform enforcement strategy and tactics. We focus here on the effectiveness of directing patrols and other resources to those geographic areas of a jurisdiction in which recent violent crime increases are heavily concentrated. This proactive enforcement strategy, guided by real-time crime location data, has strong support in the research literature and can be employed without producing resistance from affected communities (Weisburd 2016).

In the current context of diminished police capacity, deploying all available personnel, including those currently assigned to specialized units or who work desk jobs, to targeted patrols in violent hot spots would be a wise way to proceed. It will also likely require increasing overtime pay to insure adequate coverage. These would be significant challenges under normal circumstances and may appear especially formidable in the midst of a pandemic and concomitant budget shortages, but we see no viable alternative to an all-hands-on-deck smart policing response to the current crisis.

Police Reform

The third pillar of an effective response to the increase in violence is to implement reforms to law enforcement policy and practice. This does not mean endorsing demands to defund the police, a slogan with little policy import. It means embracing two of the animating principles of responsible calls for reform: (1) increasing internal and external mechanisms of holding police accountable for unjustified violence and other serious misconduct and (2) redirecting activities that the police have taken on by default, such as dealing with drug overdoses and to the day-to-day non-criminal problems of the homeless, to other agencies better positioned to handle them.

Strengthening accountability for officer misconduct in most instances will likely involve tough negotiations over changes to union contracts. That, in turn, will likely require offering incentives for reaching agreement, such as increased compensation and altered work conditions. The latter could be an effective bargaining point, because many law enforcement officials and police critics agree that the police are currently charged with time-consuming responsibilities that properly belong to others.

The police are typically the first or among the first responders to drug overdoses. Why? They have limited training in emergency medicine, whereas the local fire department and EMT services — conspicuous by their absence from discussions of police reform — have been in the emergency medical services business for decades. As far as we can tell, the primary reason the police respond to drug overdoses is because in many cases the drugs are illegal. The incidents themselves rarely involve interpersonal violence or other offenses that would require police presence for enforcement purposes.

Firefighters and EMTs are better trained and equipped to handle these medical emergencies. The police response to drug overdoses should be limited to providing security for fire department or EMT personnel in those cases where it may be needed. An added benefit of transferring primary responsibility for overdoses to fire and EMT services is that it would have little or no impact on municipal expenditures because police, fire, and EMT agencies are usually funded through the same public safety budget.

Nor should the police be the first responders, in most instances, to the day-to-day problems of the homeless and individuals experiencing mental or emotional crises. The available evidence suggests that most of these cases do not involve violence or other crimes requiring police attention. A survey of ten large police departments revealed that only about 1% of calls for service are for a serious violent crime and the most frequent requests involve no criminal conduct at all (Asher and Horwitz 2020).

Social service agencies and personnel with extensive training in crisis intervention should handle most noncriminal “problem” calls, with police serving as security backup where needed. Redirecting primary responsibility for drug emergencies and noncriminal complaints to agencies better equipped to deal with them would enable the police to devote more time and attention to their core mission: addressing serious violent and property crime.

We believe real movement on these three fronts is our best chance of stemming the increase in violence. That will only happen, however, if the relationship between the police and the communities they serve, especially disadvantaged communities, is improved in the process. In addition, what constitutes meaningful police reform may differ across communities. Some, for example, may want the police to respond to certain noncriminal calls for service as part of their peace-keeping role, whereas others would limit police presence and activity to only the most serious criminal offenses.

There is no one-size-fits-all program of police reform. But the very process of working through the details of specific reform proposals with community members should in itself contribute to better police-community relations, while also reducing concerns about the elevated police presence needed to meet the current crisis of violence.

_____

References

Asher, Jeff, and Ben Horwitz. 2020. “How do the police actually spend their time?” New York Times (June 19).

LaFree, Gary. 1998. Losing Legitimacy: Street Crime and the Decline of Social Institutions in America. New York: Routledge.

Lum, Cynthia, Carol Maupin, and Megan Stoltz. 2020. “The Impact of COVID-19 on Law Enforcement Agencies (Waves 1 and 2).” A joint report of the International Association of Chiefs of Police and the Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy, George Mason University.

“National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders.” 1968. Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. New York: Bantam.

Rosenfeld, Richard, and Ernesto Lopez. 2020. “Pandemic, Social Unrest, and Crime in U.S. Cities.” Washington, DC: Council on Criminal Justice (December).

Rosenfeld, Richard, Shytierra Gaston, Howard Spivak, and Seri Irazola. 2017. “Assessing and Responding to the Recent Homicide Rise in the United States.” NCJ 251067. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice.

Weisburd, David. 2016. “Does hot spots policing inevitably lead to unfair and abusive police practices, or can ee maximize both fairness and effectiveness in the new proactive policing?” University of Chicago Legal Forum.

_____

Richard Rosenfeld is the Curators’ Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University of Missouri – St. Louis. He is a Fellow and past President of the American Society of Criminology. His current research focuses on crime trends and crime control policy.

David Klinger is professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of Missouri—St. Louis. His research interests include the ecology of crime and social control, the use of force by police officers, decision-making in stressful circumstances, and the management of risk in challenging situations. Prior to pursuing an academic career, he served as a street cop with the Los Angeles (CA) and Redmond (WA) police departments.