by Jon Shane, professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice

Although a number of theories exist to explain why crime occurs (e.g. Cullen & Agnew, 2006), those that focus on proximate causes instead of distant, tenuous causes best inform crime prevention. Traditional disposition theories are generally too remote and attenuated to serve as a deterrent. Theories that examine proximate causes focus on the immediate situational context by analyzing the opportunities that give rise to crime, then seek measures to block those opportunities (Clarke, 1997, 1980; Cohen & Felson, 1979; Felson & Clarke, 1998). Crime is best controlled when the proximate cause is understood and acted upon as swiftly and deeply as possible.

Criminology traditionally focuses on the offender’s disposition. Biological, sociological, and psychological explanations describe the motivation for committing crime — the “why” side — but virtually ignore the process involved in committing a crime — the “how” side — the environmental correlates. Controlling offenders by reducing or eliminating the motivating factors has proved to be extraordinarily difficult. Certainly the type and quality of maternal attention (or deprivation) during child rearing is extremely important. But what can we do with that knowledge to prevent violent crime now? The sociological “root causes” of poverty, racism, education, and economics are undoubtedly important. But they do little to explain year-to-year or even week-to-week variations in crime. Whether or not the mentally ill have lower impulse control or a higher propensity for crime is not well understood, but the psychological and medical science is no help to victims today.

The basic premise of situational crime prevention is that a strong, visible defense will deter or delay a crime. It does not necessarily rely on the criminal justice system to detect and prosecute offenders.

Situational crime prevention aims to study how the physical and social environment affect crime, aggression, and disorder (Junger et al 2012). The key to controlling violent crime is to understand the role opportunity plays in committing a specific crime and to introduce measures designed to disrupt the proximate causes.

Opportunity and Crime

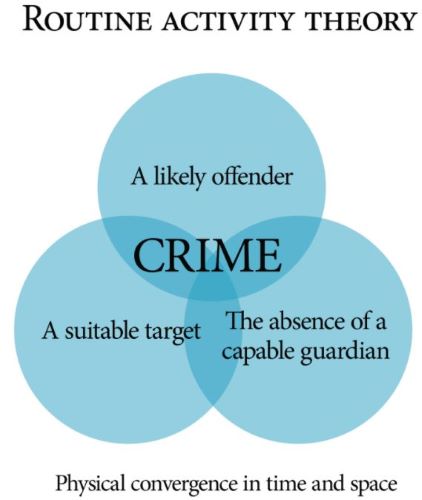

Situational crime prevention serves to deter crime by altering an offender’s judgement about the risks and rewards of committing the crime. This is typically achieved by influencing an offender’s perception of opportunity at or near the time and place where they intend to act. Situational crime prevention is a micro-level theory comprised of three overlapping “opportunity” theories of crime causation: routine activities theory (Cohen & Felson, 1979; Felson & Cohen, 1980), crime pattern theory (Brantingham & Brantingham, 1975, 1984, 1993), and rational choice theory (Cornish & Clarke, 1986). Together they provide a framework for proactively deterring offending (Holt, Blevins, & Kuhns, 2008).

Opportunity for crime arises when a motivated offender converges in time and space with a suitable target in the absence of a capable guardian. The Venn diagram of this overlap is known as routine activity theory. Opportunity means crime is possible, not inevitable. Disrupting the opportunity structure will reduce or eliminate certain crimes. The more we know about the opportunity structure — interaction between victims, offenders, environment, facilitators — the more we can design crime prevention into the social structure of life.

The basic premise of situational crime prevention is that a strong, visible defense will deter or delay a crime. It does not necessarily rely on the criminal justice system to detect and prosecute offenders (Cornish & Clarke, 2003). This process is called situational deterrence (Cusson, 1993). The core focus becomes public, private, and non-profit organizations in a position to manipulate the immediate environment in order to make it seem more difficult, riskier, and less rewarding to commit the crime (Clarke, 1980, 1997).

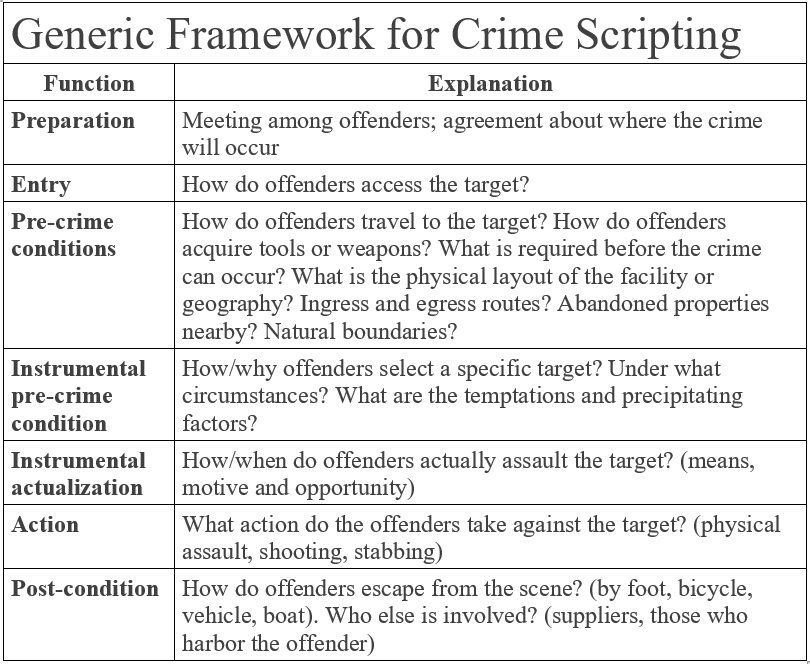

If crime is expressed in terms that are too broad then there can be little or no control exerted by society. Controlling crime is based on a deep understanding of that specific crime and its opportunity structure. For example, instead of “drug dealing,” define the crime as drug dealing in privately-owned apartment complexes or drug dealing in public housing complexes. Instead of “car theft,” consider car theft for export; or car theft for joy riding, car theft for parts. Instead of “assaults,” assaults in and around bars, or assaults related to domestic violence. This is known as crime scripting, the procedural aspect of offending (Cornish, 1994).

If crime is determined by the presence of facilitating situational factors (e.g. a suitable target, a motivated offender, and the absence of a capable guardian), then manipulating those factors is likely to reduce the opportunity for the crime to occur. Situational Crime Prevention seeks to make criminal choices less attractive to offenders. It does not attempt to improve the offenders’ social or economic position or change society’s institutions. This is a departure from dispositional theories, rooted in sociology, which explain an offender’s inclination toward crime and deviance (Becker, 1962; Tizard, 1976). Situational crime prevention views the logistics of a crime (“how”) as a more important practical consideration than the offender’s motivation (“why”). On a practical level, it is easier to design crime prevention initiatives that focus on disrupting the convergence setting or altering the environment than to change and correct the array of misfortunes that beset people throughout their life.

As such, situational crime prevention accepts criminal motivation as a constant and concentrates on controlling the immediate situational environment, which means preparing for an offender’s overt act. Preparing for that act recognizes that targets are differentially attractive based on situational opportunities that can be altered. Altering environmental temptations resides with “controllers:” 1) capable guardians who can alert authorities or take physical action to stop the attack (e.g., landscaper, private security), 2) handlers who know the offenders personally or know them by proxy and are in a position to exert control over their actions (e.g. police or local authorities), and 3) managers who have some responsibility for controlling behavior and environmental conditions at a specific location (e.g., landlords, building owners and managers) (Clarke & Eck, 2005).

Opportunity Reducing Principles

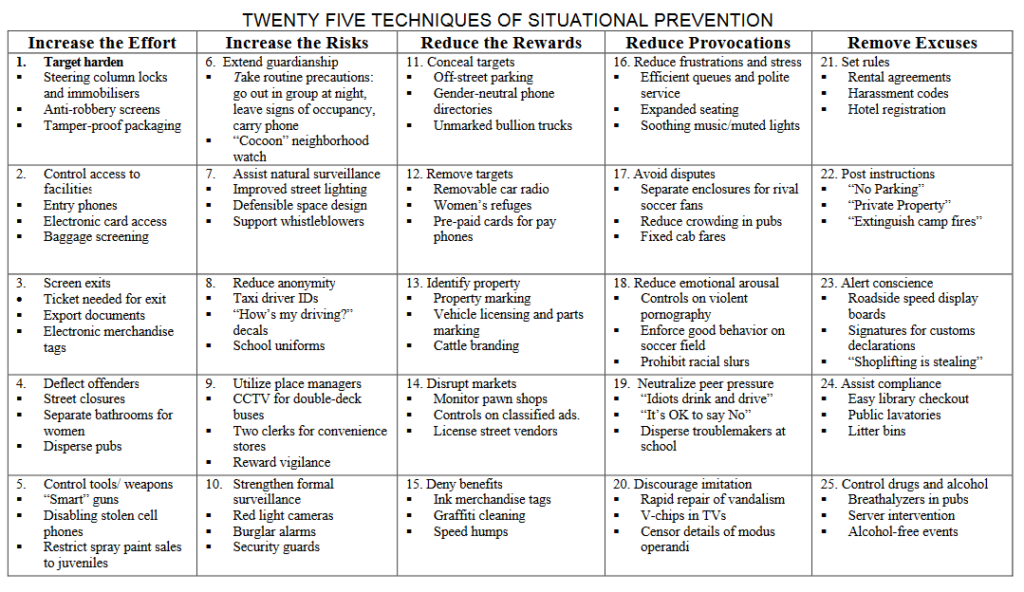

Situational crime prevention principles are classified according to twenty-five techniques grouped under five conceptual categories that describe the “mechanism through which the techniques achieve their preventive effect” (Nick Tilley, cited in Clarke & Eck, 2005, brief 38).

Since a successful crime partly depends on the offender’s perception and judgment about the amount of effort, risk, and reward, actions taken by prospective victims can influence the opportunity for crime by manipulating certain aspects of their immediate environment so that the crime becomes harder to commit, or the eventual rewards are denied. These environmental deterrents should be layered to achieve the deepest intervention possible.

Applying Situational Crime Prevention to Control Violent Crime

Although the police play an undeniable important role in crime prevention, they are not the only source of crime control. Situational crime prevention places a great deal of value on interventions that are preventive (not reactive), that do not rely exclusively on the criminal justice system for solutions. Situational crime prevention engages other public agencies, private corporate agencies, not-for-profit groups, and community resources to eliminate or reduce the problem. Deterrence relies more on the certainty of apprehension than the severity of punishment (National Institute of Justice, 2016). Detecting or blocking opportunity is more effective than crime control policy involving prosecutors, courts, and corrections with longer imprisonment terms.

It is vitally important to specifically define and analyze the crime that needs to be addressed. This means that distinctions must be made, not between broad crime classification such as assault and robbery, but between the different types of offenses with each of these categories. In terms of violent crime, ask: What type of violent crime? Domestic violence? Street robberies of immigrants? Robberies of convenience stores? Robberies of ATM patrons? Assaults in and around bars?

Success depends largely on how well the crime is defined so the opportunity structure can be disrupted at various points. Collecting information about a specific type of crime will come from official documents (police reports, hospital/emergency room data) and interviews (offenders, victims, community members, elected officials, manufacturers, business owners, see Decker, 2005).

Next, the sequential steps — the choreography — of how the crime actually occurs must be understood. Asking who, what, when, where, how and why breaks the crime into its constituent parts and provides an understanding of the crime script (Poyner, 1986). This is where resources are mobilized and responsibilities are assigned beyond the police. The police cannot address all dimensions of violent crime nor do they have the time, money, or expertise to do so.

This is a general framework for examining the sequential steps for a crime (recognizing that additional steps not shown may apply for a specific crime). This framework helps police and their partners look at the situation from the offender’s perspective. Understanding how offenders commit crimes is more important than understanding why they commit certain crimes.

Once the crime has been defined and analyzed, designing and implementing a control measure with a vast array of resources is next. The standard methodology for implementing a situational crime prevention project is based on the action research methodology (Clarke, 1997, p. 15; also see Scott & Kirby, 2012):

Collect data about the nature and dimension of the specific crime problem. Data will come from official government documents and through interviews with offenders, victims, community members, elected officials, manufacturers, and business owners. This is the time to determine who, what, where, when, how and why the crime is occurring.

Analyze the situational conditions that enable or facilitate the crime in question to occur. What are the temptations, precipitators and opportunities created by inadequately protected targets? The problem-analysis triangle can help focus stakeholders on their area of expertise. Ask “What does the problem analysis triangle look like before, during, and after crimes?” (Clarke & Eck, 2005, step 8). This will affix responsibility for individual stakeholders to ensure they are accountable for their role.

Problem Analysis Triangle

Crime facilitators enable offenders to commit crime. Crime enablers occur when behavior at places is not regulated and when guardianship is eroded. Facilitators can dilute situational crime prevention measures, so it is important to identify what role they play in the crime under examination. Evidence about facilitators can be found in police reports, interviews with victims and offenders, and by observing social situations (e.g., surveillance). There are three types of facilitators (Clarke & Eck, 2005, step 34):

- Physical. Physical facilitators are things that enable the offender’s capability or somehow assist the offender to defeat situational crime prevention measures (e.g., physical design of a building, physical layout of a public park).

- Social. Social facilitators stimulate crime by enhancing rewards from crime, legitimating excuses to offend, or by encouraging offending (e.g., group thrill).

- Chemical. Chemical facilitators are disinhibitors that increase an offender’s capacity to ignore risks or moral prohibitions (e.g., drugs and alcohol).

Examine the means for blocking opportunities for the crime in question, including the costs. Crime tends to arise because an institution — business, government agency, or other organization — failed to conduct its affairs in a manner consistent with crime prevention. Addressing a crime condition usually requires the active cooperation of people and institutions that have previously failed to take responsibility for the conditions that enabled the problem to develop. These stakeholders must assume responsibility for their role. This means to ask: Who owns the problem? Why has the owner allowed the problem to develop? What is required to get the owner to undertake prevention?

Shifting and sharing responsibility for conditions is essential for systematic and lasting crime reduction (Scott, 2005). It is also essential for reducing implementation failure, which includes: unanticipated technical difficulties, inadequate supervision of implementation, failure to coordinate action among different agencies, competing priorities, unanticipated costs (Hope & Murphy, 1983).

Implement the most promising, feasible, and economic measures. This may sound obvious, but is an important guiding light. As much as possible, always opt for solutions that can bring a rapid reduction to the problem, apply as many layers as possible to each sequential aspect of the crime, and are cost effective. This means focusing on the proximate and direct causes of the problem (e.g., the physical environment, the implements used to commit the crime, handlers, managers, guardians). Addressing “root causes,” assuming they are clearly identified and related to the specific crime at hand, may bear fruit in the distant future. However, unless and until the immediate causes are dealt with, the current conditions will continue to claim victims. Crime control techniques that should be considered at this point are numerous. Of course not all are appropriate to every given crime; different problems require different solutions. But these are some of the tools that can be considered:

- Seizing assets via forfeiture.

- Assigning police officers and social workers to schools.

- Closing streets and alleys and rerouting traffic through traffic and civil engineering.

- Using crime prevention through environmental design and defensible space concepts to systematically and permanently alter the environment.

- Adopting building construction standards to design-in crime prevention.

- Conducting crime a prevention publicity campaign.

- Repurposing, rehabilitating or razing abandoned buildings.

- Implementing a community beautification program.

- Implementing traffic calming.

- Focusing of specific offenders.

- Improving street lighting.

- Using landscape architecture and horticulture design to reduce shadows, and increase visibility and sight lines.

- Using zoning ordinances to regulate behavior and commerce in designated areas.

- Using civil abatement against property owners.

- Monitoring offenders on conditional release.

- Conducting decoy or sting operations.

- Conducting a police crackdown.

- Implementing alternative dispute resolution systems.

- Installing video surveillance in public places.

- Implementing programs to keep juveniles constructively involved, which avoids victimization.

Monitor results. This essential step of basic accountability and scientific method is too often forgotten. First, create case-control groups. This enables one to compare the intervention site (e.g., people, places, times, or events) with people, places, times, or events that did not receive the intervention although experienced the same problem. The group exposed to the intervention is termed the case group. The comparison group that does not receive the intervention is termed the control group. Comparing these groups helps determine whether a given intervention is successful and whether there is displacement and/or a diffusion of benefits. Comparison is also necessary on ethical grounds to determine if an intervention is harmful and must be discontinued. Depending on the length of the study, it may also happen that an intervention is so obviously successful that it would be unethical not to expand it more quickly. Though in the practitioner-world, these interventions are usually measured in weeks more often than years.

Next, evaluate the implementation process. Ask “Was the intervention implemented as planned and was it altered in any manner? If it was altered, “why?” Did the alteration help or hurt the intervention? A process evaluation is essential to ensuring the program was designed properly and stakeholders are held accountable. A process evaluation can reveal: an inadequate understanding of the problem, which components of the project failed and which were successful, whether displacement and diffusion of benefits occurred, and any unanticipated external changes that may have had an adverse impact on the response (Eck, 2017).

Conclusion

The criminal justice system does not play a central role in situational crime prevention. Instead, a constellation of public, private, and non-profit agencies hold the keys to reducing or eliminating specific crimes. Any attempt to control violent crime should involve an all-stakeholders approach to ensure each dimension of the criminal activity is addressed.

The police are necessary but not sufficient for a comprehensive intervention. They wield the coercive power of the state if necessary (given the dangerousness of violent behavior), but the standard police response — arrest, investigate, prosecute — is limited. It is unrealistic and impractical to believe that police and local government will prevent all violent crime. Effective policing requires collaboration and elected and appointed officials (e.g., mayors, city managers, county executives) should champion the cause (Plant & Scott, 2009).

Violent crime is a complex phenomenon. As such, it requires a thoughtful, analytical approach. Situational crime prevention has a long and distinguished history of success, all too rare in the academic world, that focuses on the settings for crime, the environment, rather than those who commit the crimes, the offenders. The approach does not attempt to eliminate criminal tendencies by improving society or its institutions. The goal is a form of deterrence, to make criminal action less attractive to offenders. This benefits the potential offender as much as society.

Resources

- Crime Solutions. https://crimesolutions.ojp.gov/.

- Center for Problem-Oriented Policing. https://popcenter.asu.edu/.

- Jill Dando Institute of Security and Crime Science. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/jill-dando-institute/.

References

Becker, H. S. (1962). Outsiders: Studies in the sociology of deviance. Glencoe: The Free Press.

Brantingham, P., & Brantingham, P. (1975). The spatial patterning of burglary. The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice, 14, 11-23.

Brantingham, P., & Brantingham, P. (1984). Patterns in crime. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Brantingham, P., & Brantingham, P. (1993). Nodes, paths and edges: Considerations on the complexity of crime and the physical environment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 13, 3-28.

Clarke, R. V. (1980). ‘Situational’ crime prevention: Theory and practice. British Journal of Criminology, 20, 136-147.

Clarke, R. V. (1997). Situational crime prevention: Successful case studies. Albany, NY: Harrow and Heston.

Clarke, R. V., & Eck, J. E. (2005). Crime analysis for problem solvers in 60 small steps. Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice.

Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44, 588-608.Cornish, D. B. (1994). The procedural analysis of offending and its relevance for situational prevention. Crime Prevention Studies, 3(1), 151-196.

Cornish, D., & Clarke, R. V. (Eds.). (1986). The reasoning criminal. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Cornish, D., & Clarke, R. V. (2003). Opportunities, precipitators and criminal decisions: A reply to Wortley’s critique of situational crime prevention. In M. Smith & D. B. Cornish (Eds.), Theory for situational crime prevention: Crime prevention studies (Vol. 16, pp. 41-96). Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press.

Cullen, F. T., & Agnew, R. (2006). Criminological theory past to present: Essential readings (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury.

Cusson, M. (1993). Situational deterrence: Fear during the criminal event. Crime Prevention Studies, 1, 55-68.

Decker, S. H. (2005). Using offender interviews to inform police problem solving. US Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

Eck, J. (2017). Assessing Responses to Problems: Did it Work. 2nd ed. An Introduction for Police-Problem Solvers. US Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

Felson, M., & Clarke, R. V. (1998). Opportunity makes the thief: Practical theory for crime prevention. Police Research Series, Paper 98. London: Home Office.

Felson, M., & Cohen, L. (1980). Human ecology and crime: A routine activity approach. Human Ecology, 8, 389-406.

Holt, T. J., Blevins, K. R., & Kuhns, J. B. (2008). Examining the displacement practices of johns with on-line data. Journal of Criminal Justice, 36, 522-528.

Hope, T. & Murphy, D. (1983). Problems of implementing crime prevention: The experience of a demonstration project. The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice 22: 38–50.

Junger, M., Laycock, G., Hartel, P. & Ratcliffe, J. (2012), Crime science: editorial statement. Crime Science 1, 1.

National Institute of Justice. (2016). Five things about deterrence. Washington, DC: NIJ. Retrieved on February 9, 2021 from https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/247350.pdf.

Plant, J. B., & Scott, M. S. (2009). Effective policing and crime prevention: A problem-oriented guide for mayors, city managers, and county executives. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

Poyner, B. (1986). A model for Action. In Situational Crime Prevention, Gloria Laycock and Kevin Heal (eds.). London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Sacco, V. F., & Kennedy, L. W. (1998). The criminal event. Toronto: ITP Nelson.

Scott, M. S., & Goldstein, H. (2005). Shifting and sharing responsibility for public safety problems. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

Scott, M., & Kirby, S. (2012). Implementing POP: Leading, structuring and managing a problem-oriented police agency. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.Tizard, J. (1976). Psychology and social policy. Bulletin of the British Psychological Society, 29, 225-233.

Weaver, G. S., Wittekind, J. E. C., Huff-Corzine, L., Corzine, J., Petee, T. A., & Jarvis, J. P. (2004). Violent encounters: A criminal event analysis of lethal and nonlethal outcomes. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 20(4), 348-368.

_____

Jon Shane is a Professor in the Department of Law, Police Science, and Criminal Justice Administration at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. He retired from the Newark Police Department after 20 years at the rank of captain.

He is the author of What Every Chief Executive Should Know: Using Data to Measure Police Performance, Learning from Error: A Case Study in Organizational Accident Theory, Confidential Informants: A Closer Look at Police Policy, and Unarmed and Dangerous: Patterns of Threats by Citizens During Deadly Force Encounters with Police Officers.