QPP 43: Elliott Averett on “Supporting” Police

Former Seattle Police Elliott Averett contributed an essay to my Violence Reduction Project. We talk about organized violence at protests, why police officers are leaving certain departments, and what that means for policing. Plus, qualified immunity!

Episode:

https://www.spreaker.com/episode/44186060

Transcript:

[00:00:04] Hello and welcome to Quality Policing.

[00:00:07] I’m Peter Moskos and continuing my interviews with contributors to the violence reduction project, which all of this can be found on at quality policing, dotcom, the violence reduction project is my effort to bring some smart people together to talk about solutions to reducing violence.

[00:00:34] And I am here today with one of the contributors, Elliott Averett, who is a former Seattle police officer and currently a JD candidate at Georgetown Law School. So thanks for thanks for joining me, Elliot.

[00:00:49] I’m happy to.

[00:00:51] So you wrote an essay entitled What Supporting Police Means, and I think it’s an important essay to have in the collection. And I’ll get into that, presumably.

[00:01:05] But I’m can you tell me what what does supporting police mean? What did you write about?

[00:01:11] I think, you know, my my main concern that I’ve seen since I and even before actually I left the Seattle Police Department. Was the fact that, you know, you can make policing can be a great job. It can be a great job. It can be a lot of fun. You can help people. And there’s a lot of things that feel good about. It can also be a terrible job and, you know, and a lot of officers, especially young officers who are or are smart, smart young officers, they come to the they want to help. They want to do the right thing. They want to arrest violent criminals and people and help people who are victims. And a lot of times at the Seattle Police Department, they will run into a wall of the department just trying to do the right thing. They’d get in trouble and be reprimanded for minor things like failing to turn on a camera in time or not filling out the right report. Right. Because this is this was what the city and the command staff had put all the emphasis on. And so a lot of great officers are quitting like they’re quitting big city policing because, you know, right now there’s a real shortage of cops. And so a lot of the best young officers, including many friends of mine, really good friends of mine, one of whom I talked about the essay, have realized, like, yeah, I can just go to the suburbs, I can make just as much money and do the same work and not have to put up with, you know, the stuff that’s going on in Seattle or Portland or San Francisco or Los Angeles. They just don’t have to do it anymore. And I think you get a sort of brain drain effect right where you go. You’re the best cops, especially your best young cops are leaving Seattle and other big cities. And that that’s what I wanted to highlight, NASA.

[00:03:17] And so, actually, maybe I can share the picture that’s in the essay to illustrate that point.

[00:03:28] Which is, as you know. A banner in a place that maybe will remain nameless, but it’s not like they’re being quiet about.

[00:03:42] Their goals here trying to get police officers from Seattle and presumably at some point that is Seattle’s loss in these other departments game. So what is different about these other departments? You know, is the pay better or is it just the the political condition from police officers perspective?

[00:04:05] Well, I’ll just I mean, I don’t have that that photos from Bellevue from a friend of mine who worked for the Bellevue Police Department. Right. Which if you don’t know about Bellevue, Bellevue is a great example of this, actually, because Bellevue, for those who aren’t familiar with the Pacific Northwest, is right on the other side of Lake Washington from Seattle. It’s a very sort of wealthy it’s a sort of medium sized sort of inner entering. It’s just a suburb of Seattle, but it’s very wealthy. It’s very nice, relatively low crime at Bellevue. They have very high standards for their officers.

[00:04:42] You know, they prefer to hire officers with college degrees.

[00:04:44] I think they give a paper a pay bonus for that. Right. And over the last round of rioting in Seattle, the cops on the charges, the city council announcing they were going to defund the police department and lay off like hundreds of officers.

[00:05:02] Bellevue went on a hiring spree and they hired many police officers from Seattle and all of these sort of mid-sized cities. Yeah, actually, the pay might be a little bit less for some of these cities. Like I have my friend who I described the essay. He went to a different city, but he took a pay cut. But he did it because he he knew he was going to be working in a city where he wasn’t going to be constantly hauled in front of internal affairs for failing to write a police report.

[00:05:31] Or he wasn’t going to talk about something minor. He wasn’t going to face an investigation. Every time he got into a pursuit that was justified, he wasn’t going to have lieutenants and captains who hadn’t been on the street in years filing complaints against them because they didn’t like what he wrote and his use of force report. And he knew that if he made arrests on felony drug cases and felony gun cases, that the prosecutors in this suburban county would prosecute them, which he liked. He wanted to feel like his job actually mattered. And so he was willing to take a pay cut because he he just wanted people want to feel like their work is important. Seattle pays very well. It’s probably one of the highest paid police departments in the country, if not the state of the state of Washington. You know, you could easily make six figures after spending five years on patrol there, just that base pay before overtime or anything else. But, you know, money isn’t everything for people people want to feel like. What they’re doing matters and they don’t feel like that, then they’re they’re going to go somewhere else.

[00:06:40] I should mention, because this is actually a podcast, though, the plan is to put it all on YouTube, that the sign I don’t know if I said it says welcome to Seattle laterals. That should be. Yeah, that’s kind of important for people listening.

[00:06:54] It’s a it’s a banner in a hallway saying Welcome Seattle laterals, meaning lateral transfers. The prosecutor part is interesting because having lived in cities all my life, I just assume it’s natural that cops. Bitch about prosecutors, is that not the case in some of these other jurisdictions?

[00:07:13] I mean, I’m sure that it is.

[00:07:17] I’m sure, you know, cops and prosecutors, despite sort of the meme or whatever, that we’re all buddies hanging out at the bar, actually don’t really get along. And I agree with you in that sense. But I think it’s a little bit different when you have a prosecutor who, you know, like in Seattle, even when I worked in King County, and now it’s even it’s even it’s even worse than this.

[00:07:39] But when I worked in King County, it was like.

[00:07:42] The King County prosecutors, I went to a train with them and they flatly told me, you know, we won’t file basically any of your narcotics cases under three grams of heroin or methamphetamine no matter what, they just wouldn’t do it like that. It’s like ours is not going to file those cases.

[00:08:02] I don’t think the public realizes that that these, you know, partly because the system has to function at some routine level. You know, prosecutors don’t look at each case individually unless there’s some specific reason to. So they make these rules, which are arbitrary, but very much determine how policing works on the street.

[00:08:22] I remember thinking specifically, there was an article today and today is April 3rd. Twenty twenty one. There’s an article today in The Baltimore Sun about residents complaining that drug dealers were actually weighing the drugs on the steps of a store and and were complaining, the reporter mentioned was the first time he heard residents complain specifically call out the consent decree as a problem.

[00:08:52] But why are drug dealers weighing drugs in open? Because the prosecutor just announced that she wouldn’t prosecute drug possession anymore. And you might go, OK, well, that’s you know, that’s a big issue I don’t want to gloss over too glibly, but many people go, well, that’s great. We shouldn’t be worried about that. There are there are reasons to worry about it related to quality of life. But the reason to worry about it is because the prosecutor for decades in Baltimore has simply defined drug arrests as drug possession. Unless there are more than a certain and it changes a certain number of units on the person arrested. So somewhere between 20 and 30, I don’t know what it is right now, but if you arrest a drug dealer, a known drug dealer, and can articulate why the person was dealing drugs, you saw hand to hand transactions, the whole thing. But if the person actually slinging or handing off the drugs, who probably isn’t the major player anyway, but the point is that it’s automatically drug possession because that person does not have more than, you know, a dozen vials of dozens of heroin or crack vials. So you’ve defined drug dealing as drug possession, and then you say you won’t prosecute drug possession. So now apparently drug dealers are like, great, we’re free to do this in public now. It doesn’t mean they weren’t dealing drugs before, but there are certain sort of informal regulation that had occurred much more when I was on the streets there, but apparently much more last week. So, I mean, this the workings of the. Yeah, most people have no clue how this sort of works and the interactions between the street and police and then police and prosecutors. So when you talk about supporting police, you’re talking about the internal system. I mean, I you know, I don’t see a blue lives matter flags behind you, for instance, because I think when and, you know, cops can be their own worst enemies, especially if you’re trying to appeal to political centrists and even the political left. But the public generally correct me if I’m wrong, you know, when they support the police, they think of supporting the police when they do bad things, supporting police unconditionally.

[00:11:06] So, yeah. Go, go, go, go on, go on.

[00:11:11] Yes, sir, I was just going to say, you know, I think that’s right and I think that it goes deeper than that. I mean, you know, it’s it’s just in my opinion, this is really simple. I mean. Do you want to have a police force that’s full of the people who couldn’t get any other job, or do you want a police force? That’s people who are do you want it to be a competitive thing where you’re hiring the best, the brightest, the brightest people, people who are thinking hard about the issues, people who are thoughtful, people who are caring, people who are motivated. Right.

[00:11:48] People in school get other jobs and still choose to be police officers.

[00:11:52] Exactly right. Like you. And I think that this is a common sense thing. I think, you know, support people. They support police. Well, you know, again, yeah. It doesn’t just mean blindly support the police, but it does mean understanding that having you know, if you make policing as a job suck, then people who have other options just won’t do it anymore or they’ll go do it in a city where it doesn’t suck.

[00:12:18] And usually that’s going to mean the suburb that pays almost as much and has a lot less crime. And it’s probably a lot safer for police.

[00:12:28] And this goes beyond, you know, I think. What what frustrates police officers is that when I was in the police academy, we had an instructor and he said. You don’t have to be right if you’re a cop, you just have to be reasonable, and I think that that by itself cuts to basically everything police do, because if you’re making all these decisions, do I stop this guy to have a good enough? Terry, stop. Should I arrest this guy? Can I ask this guy? Can I use how much force do I apply in this situation? All these things are judged by one of the legal standard of reasonableness. Well, you know, reasonableness is objective, theoretically, right, and I should add, it’s reasonable from a police officer’s perspective, which is different than the public’s perspective sometimes, but that matters in court a lot.

[00:13:22] It does. But you know, this again, this is fear, theoretically, right? Yes.

[00:13:26] Objectively reasonable is an object to be reasonable police officer do. But in practice, the persons who make all the decisions about what is objectively reasonable are going to be your chief. If you get a complaint who’s appointed by your mayor, they’re going to be your internal affairs director, who at least in Seattle is a civilian. Right. They’re going to be a judge or jury if you get sued. Right. So in reality, where you are makes a huge difference in what people think is objectively reasonable. And so, yeah, I mean, know and frankly, a lot of people in Seattle, you know, the idea there of what is objectively reasonable has kind of departed long ago from, I think, anything that would have matched up with what the Supreme Court recognized. And and it’s very frustrating for officers because, you know, on one end you’ve been told, hey, as long as you were reasonable, you can make a mistake. You’ll be OK if you make a mistake as long as that mistake was reasonable. But in Seattle. Making a reasonable mistake, you could still end up with a written reprimand in your file, you could still end up getting suspended or sued. Right. And so, you know, people would rather work in a place where reasonableness at the very least is going to be a little bit more of a forgiving standard.

[00:14:56] I joke, but I’m not joking that in the old days, not very long ago, cops actually had to do something wrong to get in trouble and even then it wasn’t guaranteed. Now cops are can get in trouble when they do the right thing, much less an honest mistake or, you know, a reasonable mistake. But that’s a big change. You know, people you can never prove causation, but I certainly think it contributes to less policing that we see in city after city. And it’s always a little worrisome to quantify less policing because you don’t want to have you know, you don’t want to just say, go stop and arrest people. So we have numbers. But at some point, those quantitative measures of proactive policing are indicative of something. And they’ve gone down dramatically in every city I’ve looked at last year post, you know. Yeah, protests, riots and post the killing of George Floyd. You know, Seattle, I looked up the numbers and again, who can say why for sure? But last year there was something close to 54 murders, which is almost twice as much as the previous. I mean, the previous five years, the murders range from 19 to 32, but they’re generally around 25 a year and then it jumps up to 54.

[00:16:21] That is a huge increase. Do you. Why did it happen, do you think?

[00:16:29] Well, I think, you know, I think part of the reason it happened is just the chaos of the rioting in Seattle, which was extreme. Even this got very little attention after it concluded.

[00:16:40] But I mean, you know, for like a month, there was a six block area of the city where the police were not allowed to go.

[00:16:47] This is the shop owner, Charles, that you mentioned earlier, which I, you know, I’m happy, wasn’t in my city, but from across the nation. I thought, hey, I was happy to see, you know, saying, OK, give it a try, maybe it’ll work. I don’t think it will. But but yeah, it what? So what happened?

[00:17:02] Can you can you summarize sort of between six six people got shot there, two of them got killed. Right. So that’s not all I’m going to raise the murder rate. But that that area I know that area because that’s where I used to work. That’s an area that would normally have two murders in a year.

[00:17:17] Right. And we have, you know, six and maybe four, three or four weeks or six shootings or two murders, maybe three or four weeks.

[00:17:24] So, you know, the level of chaos in Seattle was substantial. I do think there is some effect of the pandemic, at least in terms of domestic violence. I think domestic violence has something to do with it. But, yeah, you’ve also seen the collapse of the like the collapse of the police department in Seattle. I mean, two hundred officers and four that’s a small police department to begin with.

[00:17:47] They’re big regional variations here. What do you know, the numbers roughly off the top of your head for Seattle.

[00:17:54] So normally it was between thirty eight hundred and fourteen hundred officers. Right. And on a per capita level, that has actually on a per capita level, it’s been decreasing because the number of officers in the city has really stayed the same since, I believe at least the early 2000s, even as the city has added hundreds of thousands of residents. So on a per capita basis, it’s it’s towards the bottom. Let me just like the last comparison, if I could.

[00:18:21] Well, over the last year, what had to go down?

[00:18:24] Two hundred more officers left the department. They just either retired or resigned and went to a different suburban police department or, you know, and that’s a record setting number because in past years, I don’t think we’d had more than maybe one hundred and ten guys. You’re looking at the number of officers deciding to leave almost doubled just in one year.

[00:18:45] And it almost all happened like that last six months of twenty 20. Right.

[00:18:49] Starting in August in New York, the number of retirements from the NYPD doubled compared to the previous year.

[00:18:56] People just don’t know enough, you know, I don’t know I don’t know if those were people with decades on or younger people, but but the number of retirements doubled the number of cops in Seattle. So now it’s somewhere we assume between like 11 and 12 hundred or.

[00:19:12] That’s what I would say, I think there are some people who are, I guess you’d say, burning time before they retire, but probably are effective officers on the street right now is probably going to be around eleven hundred officers now to put that in comparison.

[00:19:26] So Seattle has a population of 720, 4000. Baltimore City is down to, I think, less than 600000 now, but about 600000 people. Baltimore is understaffed and it still has well over 2000 officers that have close to 3000 officers. When I was there and in 2001. That’s a I mean, it’s a big difference, it is per capita, you know, close to half the number of officers as some of the more staffed East Coast police departments. Now, in some ways, you can say, you know, as a taxpayer, that’s great, you’re getting more bang for your buck. Seattle still a safer city than a lot of places, you know, take.

[00:20:11] The murders are 50 for last year, which is a huge increase. But Baltimore had three hundred and fifty, you know, so these cities are extremely different and demographics and economics and everything in history.

[00:20:22] But I actually have wondered, like, I don’t understand how a police department can function with so few cops. I really don’t. At some point you how is it just you just do you often have nobody to respond. Like, I don’t get it.

[00:20:38] Yeah. I mean, if you look at the median response times for priority one calls and actually the median response time in Seattle, I’m not really sure what the national standard is, but the goal that they would set for priority ones which were in progress, assaults, burglaries with occupied burglaries, shootings, things like that. Their goal for response was a median, I believe, of seven minutes, which is a long time. I don’t I don’t even know if that’s an appropriate goal. And that has not even really been come close to been met in the last six months and some months, if I recall it. Data I saw. I don’t have it here in front of me. It was closer to like ten minutes for a priority one. I don’t want to call, but yeah, I mean, even when I worked at speed. Right. You know. And what years were you there? I was there from twenty fifteen to twenty nineteen. So I started the Academy of August of twenty fifteen and then I left in July of twenty nineteen. But I worked in the bar district on Capitol Hill for a majority of that time, which is where the chops on was later established. And yeah, there are nights that you know, we just would not do anything except go from priority one call, the priority one call and other calls just wouldn’t get answer about, you know, trespassing or disturbances. Sometimes you’d end up having to pull officers from to come from North Precinct or South Precinct to do domestic violence calls. Seattle would also put precinct area or radio zone on what they call priority calls only status, which is where they basically just tell everyone it doesn’t have sort of a life safety emergency. Sorry, we refuse to respond right now. You’re going to have to call back later. And if you look at the stats that the department put out for last year that they just recently shared with the city council, two thirds of the days of the year, something like two hundred and twenty days of the year, that that is what they did. They went to priority call status for at least part of the time. So people just. Yeah, and people would complain to me about this. Like I call the police and nobody comes. I mean, I believe you. Yeah, I believe that it happens, you know, and of course. So, yeah.

[00:23:03] I mean, the problem in having the department so understaffed. So you respond to these priority phone calls and you have to. But it means that. There’s no policing going on, it’s entire I mean, I’m assuming there’s no policing as a verb, you know, you’re not actually there’s no community interaction. There’s no quality of life policing. There’s no maintaining order. You become as a department, 100 percent reactive by necessity and. Again, you have to react, but it’s not. There’s no crime prevention going on if you’re purely reactive and if you’re not even reacting, well, of course, there’s not much deterrent there either.

[00:23:48] Yeah. And and the department would deal with this by, at least from my perspective, what it seemed like they were doing, like they would fight back on this by, like building specialized units that didn’t answer 911 calls, which, of course, is kind of like robbing Peter to pay Paul. Right. Because it just means the patrol situation is worse. But they would put officers in know precinct crime teams or on the DUI squad and the traffic unit. Right. And they would have them go out and do sort of try to do some proactive enforcement on some of the drug or nightlife issues or DUI driving. Right. But again, all your new officers started patrol, right? They all get put on patrol. That’s how they learn how to do police work. So as a practical matter, it means that all your officers, the only thing they’re learning how to do is take No one calls. So where are you going to get the officer to join the anti crime team in five years? I don’t know, you know, I think people don’t learn how to do the investigations and have the sort of. You know, build relationships with a suspect or an informant that they need to be able to have, and I was shocked, actually.

[00:24:57] So so you’re familiar with Professor Brooks at Georgetown here.

[00:25:04] And I interviewed her one week or two ago for this very podcast, so.

[00:25:10] Oh, that’s right. But, yeah, so she I wasn’t in her criminal justice class, but other students here in my section were and she had them all go on a ride along, including with the D.C. Metropolitan Police, including friends of mine and friends were like, yeah, the D.C. Metropolitan Police. So we rode along with didn’t get that many calls. And I said, what do you mean? They didn’t get that many calls? Like, they just had time to, like, hang out in the city and just kind of be a presence, which I thought that they must have like. I had thought when they told me this in my so they just heard these were law students, that they just, like, juiced it by sending them to like the boring district or something like that. I don’t think so, though, because after I talked to enough of my friends, they’re just like, yeah, that was all pretty, pretty slow.

[00:25:54] So I think that but they have way more cops.

[00:25:58] They got like 3000, 4000 cops, according to Wikipedia, just looking it up and, you know, take it with a grain of salt. Usually these numbers are slightly inflated for because it includes everybody and not just the working cops, but it says approximately thirty eight hundred officers and DC is smaller than Seattle ADC. I think per capita has the most cops for any big city, but it’s not a huge outlier. It just happens to be at the top of the list.

[00:26:26] But yeah. And then of course, DC also has a lot of other, you know, police forces because of the federal aspect of the of the district. You know, it’s like more you know, more money does not necessarily make police departments better, but you’re not going to get more for less. You can say that, you know, to a certain extent you might get the same for less with good management.

[00:26:53] But at some point, you know, it’s just like schools, you know, and all our government or, you know, bureaucracies can waste money. But usually when schools are underperforming, you don’t say, oh, let’s cut their funding to make, you know, to teach them a lesson, which seems to be how do you fund worked last year? It wasn’t I mean, you know, violence went up and a lot of defunding funding in, but it did kick in in places like New York, Seattle, Minneapolis, Portland, places that had a lot of a lot of protests. And but there was no plan. It wasn’t sitting down with police departments. It was vindictive. And I don’t quite understand how that political movement holds sway.

[00:27:39] Well, and the funny part here in Seattle is that the police monitor, who is part of the consent decree, has sort of and the federal judge overseeing the consent decree have kind of looked at the city council, which has, again, pitched this defunding plan and said you’re at risk of violating the consent decree by doing this, because under the federal consent decree, you have obligations to the court that if you just if you refuse to fund a training unit like you’re violating the consent decree, I mean, that’s just the way it is in Baltimore.

[00:28:09] The judge was very explicit saying defund is off the table. You don’t have that. It’s not your call.

[00:28:14] And and so, you know, the funny part to me, though, is that after this has kind of blown back with the mass resignations and everything that’s been happening, the chair of the Public Safety Committee on the city council, Lisa Herbold, who actually used to represent me when I lived in the city, wrote an op ed in The Seattle Times basically saying, well, we didn’t layoff any police officers. We just because the budget cuts they ended up making were relatively small, that we didn’t layoff any police officer, we didn’t defund the police. Well, that’s just that. I mean, I guess it may be technically correct, but you all sign a document and said on Twitter that you were going to cut to the budget of the police department by 50 percent. Everybody knows that layoffs are done in order of seniority. So, yeah, if I’m a police officer with five years of experience and these are my friends who quit the choices is really stark. I sit around here and wait for these people to lay me off. So I’m unemployed and I can’t pay my mortgage and I can’t support my family. Or do I go get a job in the suburbs? I mean, it’s just that simple, right? And and again, the officers who can’t leave are the guys with the I.A. jacket that’s a mile long. Guys who are on the Brady list, you know, those people can’t leave. So they’re going to stay because they got nothing. They got nothing. No other options. Right.

[00:29:32] But the good cop has left, you know, and one of the ironies I find about antipolice protests, and I’m not saying all protests are anti police, but I’m talking about anti police protests and consent decrees and a lot of oversight.

[00:29:47] Is there focused generally on departments that do a better job, which are generally the big city departments that have more accountability. And nobody is looking at these sheriff departments and, you know, rural parts of Washington State and in Oregon. And no one seems to mind, by the way, what police do there. I’m sure some people do. But you don’t hear about it. And, you know, some of that’s ideological and political.

[00:30:11] But, you know, we could be making pretty low hanging fruit, easy fixes and some departments. But instead we’re just, you know, squeezing places like Seattle and New York, which in terms of what people say they care about use of force, lethal use of force complaints do a far better job than a lot of other departments. And sort of this is this is the reward, which is unfortunate.

[00:30:36] But so how what do you say to people who say, oh, that’s all, you know, fair and good to former cops talking about how people are being mean to cops? So how do you how do you make sure that cops who do bad are held accountable? What’s how do you find some?

[00:30:56] So actually, I, I know the director of the Office of Police Accountability in Seattle pretty well. His name’s Andrew Meiburg, and he’s actually a really good guy. You know, he’s a lawyer. He’s a civilian. He and I don’t see eye to eye like we disagree more than once. I have sent an email or call him and told him that I think you’re wrong about this. But, you know, over time, one of the things that I think he has recognized is that, you know, again, I think it matters what and and something that I’ve at least something I push him again doesn’t always agree with me. But I think one thing that matters a lot is like, you know, these internal affairs processes. Right. I don’t have any problem. If you’ve got a cop who’s drunk on duty or, you know, using excessive force, I don’t have any problem running that cop to internal affairs. Whatever your internal affairs process, I don’t have any problem with a civilian review being some sort some part of that process. I think the chief should still make the final decision, but I don’t see any problem with oversight or accountability there. Obviously, cops where a cop was fired for like helping traffic marijuana to Baltimore while I was at speed and the FBI arrested him and indicted him and he went to federal prison. I don’t want to work with that guy. Nobody does. Right. He’s a criminal. I think the frustrating part is when you have an internal affairs regime that is built around these. Procedural requirements that are ridiculous, and I’ll give you a great example. So in Seattle, we had a rule in the policy manual that if somebody accused you of racism, you only stopped me because I’m black.

[00:32:42] You had to call a supervisor to the scene so they could do a biased review. Right. And this would be forwarded up the chain of command. Now, this is this is already kind of wild because you’re basically filing a complaint against yourself by doing this. Right. Most cities don’t have a requirement like this, but there’s an argument for why it makes sense. Right? I think. One time a friend of mine was doing a traffic stop on a on a guy who accused him of being racist at the time, I was just coming to as backup. I just I didn’t make the stop. I just showed up as backup. I get there. Traffic stops happening. I stand by with the driver while my friend is running his driver’s license. Right. And know he I hear him get on the radio and call a supervisor for a bias complaint. Hey, can we get a sergeant down here for basketball? So I said, OK, this is bicycling.

[00:33:36] So the guy tells me, hey, you your friend here only stopped me because I’m black. And I said, OK, OK, sir. Well, there’s a supervisor here coming to talk to you about this. I had a complaint filed against me by my lieutenant on the theory that by hearing this a second time, even though I know there’s a supervisor coming and I didn’t make the stop, I should be required to call the supervisor again. And failing to do that, this violates policy. Even though I knew there was a supervisor coming, even though I didn’t make this stop. Right. And even the Office of Police kind of ability looked at that complaint and just said, no, that’s not it doesn’t make any sense. Right. But again, when I got this complaint at the time, like a formal notice of receipt, a complaint filed by the lieutenant or the sergeant, I was just out of my mind. I was like, I feel like I’m living in crazy town here. Like I didn’t even do anything. And I’m having an official complaint filed against me like this is by my own chain of command. This is nuts. And I think that the key to having a good accountability system is just using your common sense. Yeah. People who are accused of serious misconduct do need to be investigated. But if somebody forgot to turn on their body camera for 30 seconds before at the start of a call and nothing important was not captured or somebody uses a bad word during a call or somebody wrote a report, a but they didn’t write supplement B, do you need to put a written reprimand in their personnel file? I don’t think so.

[00:35:15] I think that’s something the chain of command should be handling with coaching and counseling and and not something that is just sort of used as a gotcha by internal affairs or the chain of command. And, you know, that’s a compliment.

[00:35:32] Yeah, it’s a good answer, though. But do you know? Is this because of the consent decree, so I could think of something I just looked up, so Seattle, I believe, has been under a consent decree since twenty twelve. So we’re in year well, 10 of the consent decree, which is, you know, people who make money off of it, there’s very little incentive to finish it. So it might be a perpetual eternal consent decree. You knew nothing but a consent decree during your time there. So was it just background or does it how did did you see any way in which it affected your job?

[00:36:09] Well, so it’s funny because, yeah, this was required by the consent decree, like the example I talked about, about the bias, the bias free policing policy was something that was required by the consent decree. But my lieutenants, bizarro interpretation of this policy that somehow a sergeant needs to be called twice to the scene of a complaint that someone has already made was not part of the consent decree. Right. Like this was just poor management. It and again, there were lots of things like that with the consent decree. Like one of the things the consent decree in Seattle required was that. All issues, all all unresisting handcuffing that causes a complaint of injury should be a use of force, right? That was what the consent decree recommended.

[00:37:03] In the end, only be written by somebody who’s never had handcuffs on them.

[00:37:09] I mean, literally half. I mean, handcuffs are not comfortable. Cops know that. And people who are arrested know that. I mean, most people, I would say, complain about handcuffs for good reason.

[00:37:20] Well, but even the consent even the consent decree itself didn’t, as I read it, which I looked into it around the time I started looking in the law school, the consent decree didn’t actually require the policy that we had said if somebody says Al or these handcuffs hurt, that you had to write a use of force report about the handcuffs and the consent decree didn’t actually require that it said injury, right? Well, somebody saying my handcuffs hurt. That’s not an injury. That just means they’re in handcuffs, need to be adjusted. But the department, for whatever reason or the city for whatever reason, had taken this requirement and thought, well, we’re going to turbocharge it. And actually, towards the end of my time at Speedy, like this was one thing. This is one of the things that people would actually write in their exit interviews when they are quitting. They like I’m tired of writing a use of force report. Every single time I arrest or detain somebody.

[00:38:09] It’s crazy like and it’s a separate report you have to write. Finally, the department got rid of it in like late twenty eighteen. They said, yeah. Actually all you have to do if they complain of handcuff pain is notify a sergeant. Right. You don’t actually have to write a separate report anymore. It’s not a use of force anymore. But again, this this went on for years, like this was the official policy for like five or six years at speed.

[00:38:39] So did this contribute to why you why you left or. I guess the question is, why did you leave?

[00:38:44] Yeah, I mean, it did contribute to it. I mean, ultimately, like, I had always been interested in going to law school.

[00:38:49] So I you know, I did my trial and stuff when I was an undergrad and I had I took the LSAT and just I thought, well, I’ll take the LSAT. I think I was at the point where I was either going to leave and go to a neighboring police department or I was going to go to law school and I.

[00:39:12] You know, I got accepted to Georgetown, and that’s my target to have an opportunity to pass up, but the yeah, I mean, it was a big frustration of mine working there. And more than once, I thought about putting out a lateral application, even went to some suburban police departments and did ride along with friends of mine who work there, thought about quitting because I didn’t want to. I wanted to do police work. I didn’t want to write. All these reports and and constantly be under investigation for tiny mistakes.

[00:39:54] And you’re a good writer. So, I mean, I also think a lot of people don’t understand this is before I’m talking, you know, I quit the police department almost 20 years ago. The amount of paperwork is is shocking, both in its volume and and it’s sort of, you know, redundancy and futile illness.

[00:40:16] One of my goals when I quit was that if I can somehow find a way to to to edit the Book of General Orders or patrol guide, whatever you call it, in various cities and reduce paperwork, I’ll have done done God’s work. I haven’t succeeded in any of that. But usually more forms are simply piled on, you know, on other forms. It’s never that you act and you end up just having a large chunk of the workday is just spent writing reports and and you and I can both write well.

[00:40:48] But a lot of cops, when no cop goes into the job wanting to become a report writer, but, you know, some of them are worse than others at it.

[00:40:57] Yeah. And I’ll just give an example of this, because it’s something I saw many times. Like the report situation actually contributes to the staffing issue. It’s so bad. And so, like, I’ll give an example.

[00:41:06] So we were required to write a separate if you stopped someone on a Terry stop, you’re required to write a separate Terry report for the rest of you, required to write a general defense report. If you use force, you’re required to write a use of force report. If you use type to force like punches or a taser, every officer who was there try had to write a witness statement. Right. So you’d have a situation where maybe you had a guy who was suspected of, I don’t know, a shoplifting or a robbery or something. An officer finds that guy tries to do a terrorist up on them. He runs officers chase him, he gets arrested. Maybe he pulls out a stack or something he’s brandishing at a group of cops and they tase him, you know, five or six officers. Right. Are there and witnesses? Well, the amount those officers are basically done for the day. I mean, the amount of paperwork that they’re doing on a nine hour shift, I would see this happen where people were writing it. We call it type two use of force report. Everyone who witnessed it has to write a witness statement. Everyone obviously people have to write felony statements for general offense report. The main officer has to write the general defense report. You have to write Tarasoff report. You can take a group of five or six cops if there was a type to use of force, which again, is not lethal force or anything, it’s like punches or a taser or OK, spray. You’re taking five or six police officers off the street for probably the rest of the day.

[00:42:38] And that’s like a whole squad at speed.

[00:42:42] Like that’s a whole area. That’s a whole sectors where the cops who are just not available anymore and the amount of paperwork is is enormous. So and it’s yeah.

[00:42:54] It’s not just cops complaining about it. It’s it’s a serious hindrance to the job, to what the public thinks they’re paying police to do. Did you want. Do you have any thoughts on less lethal force versus going hands on or how you were trained? Seattle was sort of on the cutting edge of the reform movement to and correct me if I’m wrong to sort of discourage cops from going hands on. And I’ve always been I don’t think I’ve been skeptical of that, I’ve been critical of that because at some point you got to grab the person. I prefer to do it sooner rather than later.

[00:43:37] Were you trained to base Wendy’s voluntary compliance and or request for voluntary compliance and and low level force grabbing the person begin?

[00:43:48] I mean, one thing that there was definitely a thing in Seattle was that. The vast majority of officers did not want to get into use of force by themselves like this is one of those things that wasn’t technically in a policy. Right. But you could really expect that if you grabbed on to someone and you were the only cop there, you were going to get a complaint filed against you for desperation, for failure to de-escalate, because the escalation policy says you should get more resources, you know, stabilize the situation. Of course, this is not always possible. Right. Like, sometimes somebody is running away from you. But I had a friend who he was trying to stop a car prowler. The guy ran down a flight of stairs. He was the only cop out there. He got into a fight with that guy on stairs by himself in a pretty remote part of the precinct and went off the radio. We thought he was dead like it was a scary situation. We got there to find out he’d won the fight and the guy’s in handcuffs. But he got, you know. You’ve got a complaint filed against him for failure to de-escalate, and I think he ended up getting like retraining from that because he was you know, this was such a strong thing in the department that you shouldn’t go hands on someone by yourself. Now, there’s merit to that. I think it is dangerous to do. But to punish officers for doing it in a situation where it’s like either I do this or a criminal gets away, I think is a.

[00:45:14] A difficult you put people in in difficult situations, you know, in cases where people just say, fine, let them, they can run.

[00:45:21] I’m not. Oh yeah, absolutely. Yeah, there were definitely times like that. Like there was a case where I, I worked on as a detective where an officer had. You gonna flag down about a shoplifting suspect and he had just, like, run and she just didn’t chase him? I mean, he was also much larger than her. So it was probably also a safety issue. Right. But, yeah, that that definitely happened. I did that at one point when I was new because I was out with I was waiting for backup to contact a guy. And I had been told, don’t contact the guy without backup or you’re going to get in trouble. And I you know, these people were flagged me down. And there’s a guy who did a car problem. He’s right down here. And I just didn’t I said, I have to wait for backup.

[00:46:08] I just waited and the guy got away and it was safer for me to do that.

[00:46:15] But I wasn’t really doing my job. So, yeah, I think that is an issue when it comes to less lethal force, I think. As a general thing. Too many officers are like reliant on. Tasers, I think that know, I did that once a week, advanced defense, or it’ll be a week long defensive tactics, training that was all hands on staff and the time that the department offered. But most people didn’t get that training. Is it A, straight baton or, B, expendable? So we train with the I always carry a straight baton.

[00:46:55] I didn’t know they were still out there. I’m I don’t know if you know this, but I am a huge fan of straight Bratton and and believe it needs to come back for actually I feel like what I had because I think I bought it.

[00:47:07] It’s it’s an old style like Swivel SBN tune that I got from some guy, which is a Baltimore word.

[00:47:18] And you can see you can swing it without breaking your kneecap.

[00:47:21] I can’t you know, I can’t I can spin it and like I can spin it around once and catch it. But I can’t. I can’t. That’s the easy move. Yeah. I can’t do anything more than that. I tried for years to learn.

[00:47:34] I like batons and I like history and I like old stuff. And that was actually legal legalizes and the right word, but permitted again when I was there under Commissioner Ed Norris and I really wanted one. And I at some point I said the fact that I like it as not I didn’t feel comfortable using it, so I did not get one, but I wish I had one.

[00:47:56] Yeah. I mean, a lot of people carry the collapsible ASP’s, right. But a lot of cops are issued batons and not given a lot of training, especially compared to like if you ever see see the British police use batons. They’re not given a lot of training on how to use at the time. I only carry the straight Bratton because I did this extra training with it and I felt comfortable if I had to use it in a fight.

[00:48:17] But a lot of people didn’t. And I you know, we did have really good training, like.

[00:48:28] I think having cops get more training about how to win and a hands on fight is probably the number one thing to do to reduce shootings and injuries to suspects.

[00:48:38] And this is to me, this is crazy because the only guy I’ve ever heard says is Joe Rogan. Like, I was listening to Joe Rogan’s podcast and he’s like, all Compstat have a purple belt in jujitsu. And I’m like, you’re right, Joe. We should like we should have that. Because, you know, if you’re fighting with someone one on one and your approval belt in jujitsu, the odds of that person are going is going to be able to take your gun or get to another weapon are so much lower.

[00:49:01] But, you know, and we would have, you know, some jujitsu based training moves that we used at speed. But the amount of time I mean, I think I think we got like four hours a year of was the standard of use of force training. And that’s just not enough. I mean, it should probably be a quarterly thing and it’s probably at least a full day.

[00:49:22] This is the nitty gritty stuff that can actually make policing safer for everybody. My training, it was specific Guy Brand called Kogure, but it was basically basically jujitsu training.

[00:49:33] And it wasn’t enough to make me an expert in jujitsu, but it certainly helped and gave me a, you know, enough confidence to do my job, but not too much to get hurt by thinking I could suddenly handle situations alone. But yeah, cops end up shooting suspects when the cop is afraid or losing a fight. And, you know, cops don’t have the luxury of losing a fight. So, you know, you have to win. And usually that’s from superiority in numbers. But it could come from the baton. Like, I never actually hit anyone with my baton because it has such a fabulous deterrent effect. And, yeah, that that’s important to mention, I think. But boy, did I use it a lot. And I mean, I thought of this last year when I was when protests were going on. There tends to be there’s a trend to take away less lethal options from policing. Well, that leaves lethal options. I mean, the point of less lethal weaponry is to not kill someone. And I would constantly see people, you know, getting up and getting too close to cops where cops have to stand in a line that is bad for policing and it’s bad for peaceful protest as well. But harms are a great way to keep a couple of feet between you and somebody else. But they don’t I don’t you know, you don’t see them used anymore. And so that’s, you know, so the point. Yes, of course, anything can be misused. But what’s the alternative? The alternative right now, I don’t see a good alternative. Ish, but I don’t. Can’t tell if it’s too much.

[00:51:14] The city council in Seattle had actually banned completely in July of last year, they had banned pepper spray that banned tear gas. They had banned 40 millimeter launchers. They basically banned every single less lethal that the city owned except for batons. And there was a huge protest targeting the east precinct where I used to work on July twenty fifth. And my friends who are working there were like, yeah, this ordinance goes into effect. We have to put all our pepper spray in lockers. And we all we’re going to have his batons and guns and they’re going to come here and attack the precinct, which they did, and actually use a bomb to blow a hole in the side of the precinct. And at the very last minute before the riot started, I think was the night before, the federal judge in the consent decree had enjoyed this ordinance, recognizing that actually forcing a bunch of police officers to deal with a crowd with only batons was going to lead to way more use of force and probably violate the consent decree.

[00:52:19] So the ordinance was enjoined, but had that actually gone into effect right before that riot?

[00:52:27] I don’t know what would have happened. I think people easily could have been killed. I mean, this was a riot where people showed up with a van full of explosives and their own ossy mace masks, body armor, shields that was later seized by the arson and bomb squad unit. Right. Says it blew a hole in the precinct that this was an outright riot.

[00:52:50] And if you went into it with only batons and nothing else except for your gun, I don’t know what I mean. It would have been. I don’t know, it would have been, but this was that was a progressive on the city council demanded that unanimously passed the Seattle City Council because they thought, I guess, that they were sticking it to the police and not just making everything way worse. You know, I don’t I don’t know.

[00:53:14] But, yeah, the I’m not in that situation you’re talking about, I say the advantage to a Bratton for a lot of those other less lethal weaponry, you actually have to use them for them to be effective. I mean, sometimes you have to use them. The baton has a fabulous deterrent effect that holding up a can of mace doesn’t have. A Taser has some deterrent effect, too. I’ve never used one, but I hear that a Taser can serve as a deterrent for compliance. But in a crowd situation, all that breaks down. You know, that’s part of what you know, what bothers me after all of the unrest last year and the storming of the Capitol building in DC in January, I still don’t hear. And maybe, you know, there’s a lot of things I don’t hear, but I don’t hear any talk about how we’re supposed to police crowds this year and next year. You know, they say, you know, I was planning for the last battle, but I don’t even see that going on right now, policing crowds that are hostile or, you know, crowds that have hostile elements in them because it doesn’t have to be most people. It has to be some people. I don’t know what the answer is. And I don’t hear these like it’s what do we think? It’s not going to happen again. I would like these things to be discussed before rather than just simply Monday morning quarterbacking, which, of course, has to be, you know, you need action after event reviews and all that stuff. Those are good. But what’s going to happen in the next, you know, if that exact same thing happens this year and I don’t I don’t think police departments preparing for this well enough or certainly those who are saying we need better policing, you know, which that call spans the political spectrum, I think. But where what is what does that mean? And I don’t know.

[00:55:07] Yeah. So let me can I can I share something with you on the screen here, Peter?

[00:55:12] I’m sure our listeners will love that. I think you can. I’ll give a narration as you do it.

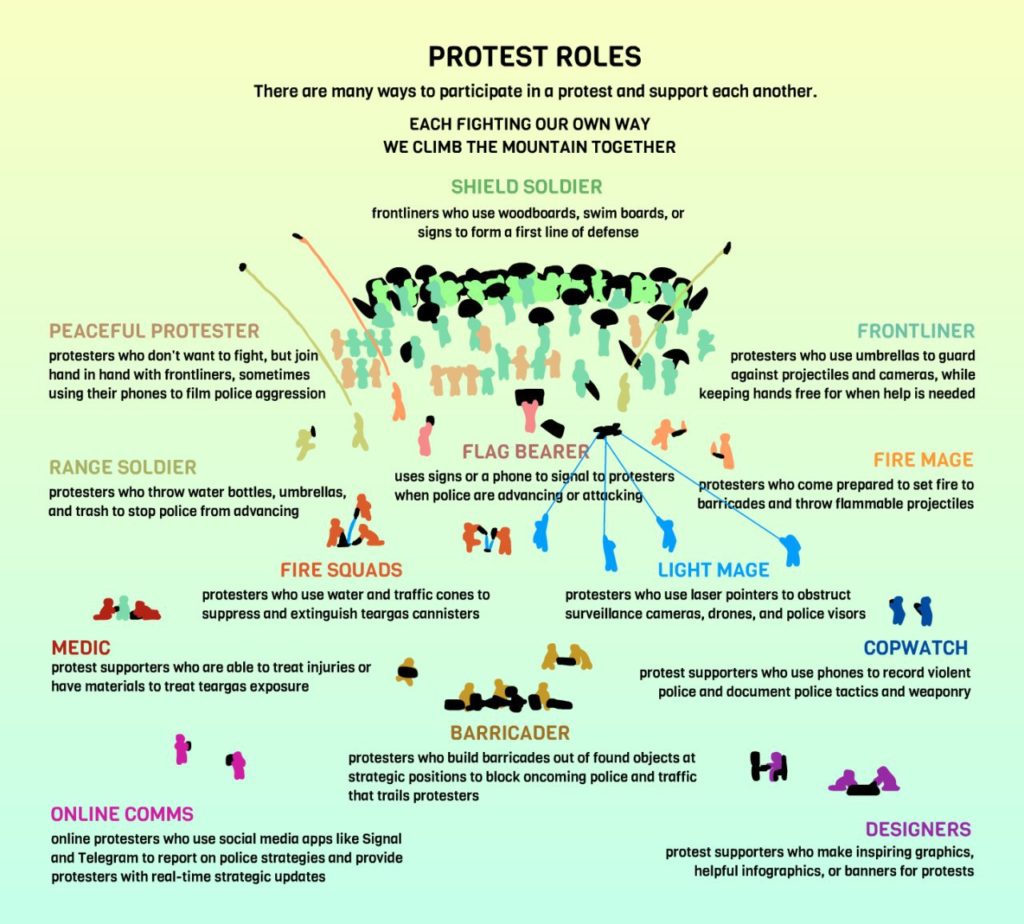

[00:55:17] Yeah. I mean, I’m just going to I’m just going to share this real quickly, because this is something that was filed in a court document after that July 25th. Can you see that? Yeah. This is something was filed in a court document after the riot was talking about on July 25th. And this is something that was being shared on social media by anti police protesters. And it says protest rules. And you can see it says Shields soldier. Right. People holding up shields and umbrellas in the front, you know, peaceful protester, protesters who don’t want to fight but sometimes join hand in hand with front liners. And then behind them, they have people who they talk about, they call fire squads, barricade or light mage, people who are shutting down less lethal weapons, people who are pointing laser pointers at police officers, people who are building barricades in the roadway, people who are throwing objects. Right. So this was something that the anarchists in Seattle and Portland at least, are an organized group of people and they deliberately use large protests. And I’ll I’ll shut that down.

[00:56:28] I’ll put that up that graphic up on. I took a screenshot of it. I put it up on the podcast episode of QualityPolicing.com.

[00:56:37] Yeah. They’re deliberately using these crowds.

[00:56:43] You know, the peaceful crowds as a means to, like, attack officers, right, and then they film the response because they know what makes police look bad.

[00:56:56] So I think that the end in the capital, the capital riot situation, wasn’t even that like it’s just a mob of people just attacking the cops. Right. Like there wasn’t really a lot of peaceful stuff going on there from the videos I saw. So, yeah, I don’t I don’t know. Again, like, I hear people say things like, you know, police should escalate the crowd or something. I just don’t know how you do that. Like, I’ve desolated individual people before and like a standoff with a weapon or, you know, making an arrest. I don’t know how you de-escalate a crowd of, like, angry people who are throwing things at you. I just don’t know how you do.

[00:57:35] You know, I think well, hopefully you to de-escalate it before you get things thrown out.

[00:57:41] I think you can de-escalate a crowd, but it depends on the crowd. It has to be a crowd. If the if the crowd it sets out with a plan and a strategy to attack police and provoke a response, there’s no de-escalation. There’s going to work because they have a plan and it’s not to be deescalated. And that, you know, so that that’s a different kind of situation from a bunch of people angry for some other reason. You know, it could be any reason, but it’s not. At some point, though, it may become focused on cops. That’s not the point of the anger. So, you know, certain sons, you can talk to, somebody who’s instigating perhaps, you know, it doesn’t always work. But but the de-escalation sort of has to happen at an individual level. And these cases now many people say and there’s of course, if you are a peaceful protester, you often don’t you may not see what is happening that what cops are responding to. So go, well, I did nothing. And suddenly, next thing I know, there’s tear gas flying near me or, you know, rubber bullets potentially. So that person, you know, and not without it’s not you know, not without justification, says the cops provoked it all. Everything was fine till the cops showed up. You hear that a lot. And sometimes that’s probably true, by the way. But other times, well, everything’s fine, except for that store that was the windows were broken, was looted and was about to be set on fire. Maybe you didn’t know about that. But I’m also willing to say at some level, just cops aren’t punching bags if cops are there and people, you know, cops have to be able to respond. And it’s tough in a crowd situation because you’re trying you know, it might just be a small percentage of the crowd, but. You got you got to you got to arrest him and you have to prosecute him at some point, that doesn’t happen either in Seattle. It seems.

[00:59:36] Yeah, I mean, I think one of the things that frustrated because you’re right about the dynamic of people who are actually innocent people in the crowd thinking I just got tear gassed for no reason. Right.

[00:59:47] I think the way to solve that is and this did not always happen in a lot of situations last summer. And I think it led to a lot of the problems. I think the way he saw that is you have a statute that makes it clear once the violence at a protest reaches a certain level of, well, somebody is a police commander, is authorized to give a dispersal order, and that dispersal order should be really loud and they should give it two or three times very loudly. You need to disperse in this direction, disperse in this direction, disperse in this direction. If you don’t, we’re going to use less lethal force. I saw videos from Portland where they did this repeatedly. Right. Nobody in that crowd thinks, oh, I’m cool just to stand here. Like, you need to make that really clear to people. Look, you stay here, you know, you’re subject to being arrested or having force used on you. And police commanders have to be willing to make that decision. I think a lot of police commanders find this to be a very tough choice because they don’t want to be the guy who, like, kicked everything off by issuing a dispersal order and then issuing the use of force to to enforce the dispersal order. But ultimately, the only way to prevent the dynamic of people being like Faustus was just used on me with no warning is to give that order and that notice, because otherwise what’s going to happen is the bad actors in the crowd are going to attack the police. They’re going to escalate things enough to the point that some cop unloads a can of spray. And that is going, you know, maybe he’s trying to hit the attackers, but he’s going to get other people. That’s just the way it works. And that’s going to kick things off. That’s going to kick off a real shit show. And if you if you’re at the command level, the instant command level, if you’re on top of that, I think you can prevent that. But it’s a hard decision for commanders and I don’t know if it always gets made.

[01:01:44] Correctly, I’ll say.

[01:01:47] So you’re saying you’re in law school now at Georgetown, you mentioned Rosa Brooks before I read her book, Tangled Up in Blue Policing.

[01:01:56] The American city interviewed here, interviewed her here not too long ago because she’s a professor there. I won’t ask what you thought of her book. I don’t. But what do you think of Georgetown Law School? And I’ll leave it there.

[01:02:13] Yeah, I think I think Georgetown is is great. I’m sorry.

[01:02:17] Let me just say I liked your book. I made that sound like there are bad things to say that I wasn’t saying. Let me just make that clear.

[01:02:24] No, I haven’t. I haven’t.

[01:02:25] And I haven’t read Professor Brooks book yet. So I think the law school is is a great opportunity. I’m happy to be here. I think law school in general has taught me that the dynamic among attorneys, including law professors and this is obviously doesn’t apply to Professor Brooks because I think she has the hands on experience. But a lot of law professors and and lawyers in general don’t understand what police do and they don’t understand what police do do because they. You learn about policing in law school by reading a casebook, the casebook is going to have cases that all start a story like this way. The story goes. The police arrested this guy and collected this evidence. And now we’re litigating the evidence whether it should be admissible or whether they violate the Constitution or it’s a story about the police did something and then they got sued. And now we’re litigating this lawsuit against the police.

[01:03:27] And it’s an academic version of the viral video, I mean, by definition, something questionable happened or you wouldn’t be reading about it.

[01:03:35] And even if nothing questionable happened. Right, even if you have a case where the Supreme Court affirms what the cops did, you know, nine to zero. Right.

[01:03:41] Because they decided everything was OK, even if you have cases like that where the cops did everything right. It doesn’t.

[01:03:51] Actually represent what you’re doing as a police officer, like 90 percent of the time, I mean, I made an arrest. Less than once a day, and I was probably one of the more proactive officers, right, in terms of looking for or people with warrants and stuff like that, some sometimes I would go weeks without making an arrest because making an arrest is like a big investment of time energy. And as a police officer, you can solve most of these little problems. Just, hey, you’re trespassing, Jimmy. Just get out of here today, OK? He’s gone by now. We’re done. The calls over. We closed it with call notes and move on to the next problem. Neighbor dispute. Just try and work it out, you know, solve these issues and move on. Mental health issue. This person accepted a voluntary transport to the hospital now. Now I’m moving on. Now these things are going to be a court case ever. They’re never going to be a court case.

[01:04:45] And so lawyers get this weird view of policing where they believe that police are like an extension of the prosecutor who are just out there to, like, sort of intake people into the criminal justice system. And I think you’d probably agree with me that that is probably a very it’s a part of what police do, but it’s probably a very small part. At least that was my experience.

[01:05:08] Yeah, absolutely. I agree with that. And it’s that’s why I don’t it’s not that these other things don’t matter, but if you don’t understand what policing is, should be and could be you, you’re missing the big point. That’s not what cops do. There’s a lot of discretion in policing. The idea is to resolve things without formal sanction. And most things are, as you pointed out, and they don’t. Yeah. So no. Yeah, yeah. It’s a good point that the people talking about policing are really talking about a tiny fraction of what policing is. And then extrapolating, thinking that’s. That’s the important part, yeah, and I think we’re taking some away, someone’s freedom is important, but it’s not the main part of the job.

[01:05:50] Right. And the rules that you put in place to govern that stuff is going to govern how everything else get resolved to that. That didn’t make it into the formal system. Right. Or not resolved. And I think that the one one thing I’ll say is that this leads to and I think a lot of police executives are guilty of this, too, right.

[01:06:12] Like, you know, Marilyn Mosby announcing her thing where she won’t arrest people, she won’t prosecute people for drugs. Now, I don’t know how the situation works in Baltimore, but like we knew that our prosecutors in Seattle had the same policy, that they wouldn’t charge people for drugs. We didn’t care.

[01:06:31] Like if we thought that somebody needed to be arrested for possessing drugs or that they were dealing or whatever, we just arrest them.

[01:06:39] Right? I mean, because the law was still the law, you know, and we have our own independent discretion. We don’t take orders from the prosecutor. And I think that’s entirely appropriate. Like police, police are exists to solve a different set of problems than what prosecutors exist to solve. So even if it is entirely appropriate to decline every single criminal charge you get with less than 30 units of heroin. Right. That doesn’t mean it’s not appropriate for police to make an arrest at all. And I think sometimes that really important distinction in law school gets obscured. Right, because people think the police are just an extension of the prosecutors function and they’re not. Not at all.

[01:07:20] I would say your experience in Seattle on that was identical to my experience in Baltimore. But I do hear from New York. And look, I was I’m not a cop here and certainly not a lawyer, but I know a few. It seems that the prosecutors in New York City and five of them for each county have more control over policing. In that sense, the police can. One of the prosecutors says we’re not going to charge the police, more or less will fall into line and I don’t know if it’s true or not, but they said, yeah, well, if we keep arresting people, knowing that they won’t be charged, it can come back to us as harassment and various other legal issues. And I don’t know if that sort of urban folklore, but I’m here in New York.

[01:08:01] There’s a bit more of. Yeah, basically police having to follow the rules of the prosecutor.

[01:08:10] I mean, and a lot of police do, I think to a large degree, like a lot of police executives and police officers have sort of internalized this, like they’ve internalized the idea that if the prosecutor won’t prosecute it, it’s not worth my time to make this arrest.

[01:08:28] And I knew a lot of cops who thought that way or they would think that they were going to get in trouble for making the arrest. Legally, I’m not sure that’s correct, I mean, probable cause is probable cause, just because the prosecutor declines the charge doesn’t mean that you’re I mean, sometimes, for an example, like sometimes I would arrest people and I didn’t even want them to be charged.

[01:08:51] I mean, for example, you know, I got you guys fighting at a bar. You know, sometimes we’d arrest one or both of them just to kind of break it up if they wouldn’t break it up on the street. But then we would just tell their friends, like, just come get your guy from the precinct. We’re not going to book him into jail. But you guys need to go home and they would do that. And then we write a police report that says we arrested him for this reason, but then we let him go.

[01:09:12] And if if a prosecutor had actually filed criminal charges over one of those incidents. Which they didn’t, as far as I know, I would have been kind of mad, I would have been like, why did you do this? Like I this was resolved. Those guys didn’t that didn’t need to happen. I’m sure it was a crime. But but now it’s been solved actually unarrest people in effect.

[01:09:34] Yeah, we would unarrest people know that that is that not that’s news to me.

[01:09:40] But I mean, I certainly like the Compstat. I mean, many things are abated by arrest and, you know, that’s that’s it. Problem solved. And yeah. But, you know, once once the handcuffs went on, they rarely went off on our end.

[01:09:53] But that seems like a good resolution to a lot of a lot of things.

[01:09:58] Yeah, I mean, and it was probably it’s a little different in every city because of how the system is structured, but for us at least. Right, we would have to transport someone to the precinct for processing and then transport them to the jail for book in. But we could terminate this process at any time if we wanted to. I mean, we can decide, you know. We’re just going to let you go from the precinct and refer the charges to the prosecutor. You know, we could decide to let someone go and he still, of course, had to document the arrest. And there was always the possibility that a prosecutor would file charges. But but, yeah, we would arrest people at times.

[01:10:37] I forgot what time we started this, so we probably should be wrapping up. But I do want to ask at least one of a few other things. But what have you learned in law school that you wish you’d known when you were on the street? Oh, man, if anything, yeah, I.

[01:10:59] I wish I had known how lawyers think about this stuff.

[01:11:03] I wish I had known that, because now that I’ve spent so much time around lawyers and law students and seeing how this process works, I know how lawyers see this and.

[01:11:16] I didn’t know that as a cop, and it made a huge difference when I was interacting with judges or defense attorneys or prosecutors, right. And now that I know kind of what I said before, well, how do lawyers learn about policing like now that I know that that would have been tremendous, tremendously useful for me a few years ago.

[01:11:38] What, um, what are your thoughts on the class differences, social class between policing and law school?

[01:11:47] I don’t know. I don’t know how much I should say about this, but there is a huge class difference.

[01:11:53] I mean, at the end of the day, people who are lawyers and you can see this even in the legal structure of the legal regime. Right. Lawyers get if you’re a judge or prosecutor, you get absolute immunity. If you’re a legislator, you get absolute immunity for any sort of laws that you pass that are ruled unconstitutional, even if you work in the executive branch.

[01:12:15] And it’s like if you’re working in a federal agency doing administrative violations or whatever, a lot of those people get absolute immunity. The president gets absolute immunity bar committees that decide what, you know, lawyer discipline a lot or or bar admissions. A lot of them get absolute immunity. Cops don’t get absolute immunity. Cops get qualified immunity, which is not as powerful as people think. Right. And there’s not to move right now that actually. Yeah, and now they’re trying to take it away and I’ve actually been looking through I mean, it’s actually one of my side projects. I’m hoping to write a law school note about this. But, you know, if you go and look through the cases of the Supreme Court deciding, OK, well, the prosecutor gets absolute immunity, but the police get qualified immunity, there’s no principled reason for this distinction. Right. It’s just because they think the lawyers are nicer people, you know, and we can’t you know, the lawyers are nice. The lawyers know, you know, the lawyers know the rules. We can’t believe that a lawyer would ever lie to the court or commit misconduct. That’s beyond the pale, incomprehensible, but believing that a police officer could do it. You know, even the Supreme Court in the 60s certainly believed that that would happen. Right.

[01:13:29] You describe actually for me, but for everybody. So total immunity actually means just what it sounds like, as prosecutors can if for whatever reasons they have, they can maliciously prosecute people. You know, they can and they’re immune. They’ve total immunity. Total immunity means just that. Mosby actually had a case brought against her for the prosecution of the officers involved in the death of Freddie Gray.

[01:13:57] And her prosecution was so egregious that the case did actually make it up to Maryland’s top court, where eventually they said no, sorry, total immunity means just that.

[01:14:07] But it was one of the rare cases where it was challenged. What is qualified immunity and why do we care if it’s taken away from cops?

[01:14:16] So qualified immunity just is basically a rule that says if you’re a police officer and you broke the law, you can’t be held liable unless the the law in question was clearly established at the time you broke it. Right.

[01:14:32] And I think the the original case from which qualified immunity comes was Pearson versus Ray in nineteen sixty seven.

[01:14:39] Where. The Supreme Court had basically there had been a sort of civil rights case where some officers had made arrests based on like a disorderly conduct law in the South. They’d arrested civil rights protesters. That law had been challenged in court. And I believe the Supreme Court had invalidated the statute as being unconstitutional. Right. So the whole statute itself was just tossed out. So then the civil rights activist turned around and sued the judge, the prosecutor and the police officers who had arrested and prosecuted them under this statute.

[01:15:17] And the Supreme Court, that is where the qualified immunity regime sort of comes from.

[01:15:21] Now, the judges and the prosecutors in that case got absolute immunity, right? The court, the police officers got qualified immunity on the theory that, look, you know, the officers had no way of knowing that we are going to invalidate this statute. Right. Which I think is entirely reasonable. I mean, you know, you’ve no way of knowing.

[01:15:40] I mean, the Supreme Court in Washington state recently invalidated the state’s entire drug possession statute.

[01:15:46] So just simple possession was not a crime anymore. And as far as I know, it still isn’t. So if you’re a police officer who makes an arrest for drug possession and then two weeks later, the Supreme Court rules drug possession arrest are unconstitutional.

[01:16:03] Should you be getting personally sued for that? I think the answer is no.

[01:16:07] That seems like a no brainer. But isn’t there more to it than that?

[01:16:11] Well, so a lot of the qualified immunity rhetoric goes around how you define what is clearly established. And some courts have taken a very narrow view of what is clearly established.

[01:16:21] And like there was a case that a lot of the libertarians got very angry about, where some officers had got a search warrant for a guy’s business to seize some coins. They did serve the warrant and seize the coins, but then they stole them. Right. And and then he sued and said, you stole my coins. And they said, well, we have qualified immunity, right? Well, I think a lot of people, they get upset because it’s like everybody knows that stealing is wrong. Right. And the Court of Appeals did grant those officers qualified immunity. I think that’s just a wrong decision. I think that the way that it was originally laid out in one of these Supreme Court cases was that qualified immunity protects everybody except for those who are plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law. And I think if you’re a court, that’s the standard you should hew to an officer who who knowingly violates the law. I have no problem with him being personally sued. Right.

[01:17:22] But the a lot of times the law in these areas around the Fourth Amendment and everything else is constantly shifting.

[01:17:29] And if you just say no qualified immunity at all. Then you’re just going to have a floodgate of litigation and one day that never gets talked about in the qualified immunity discussion is that the civil rights statute that allows for these lawsuits to be filed for constitutional violations?

[01:17:50] It adjusted nineteen eighty nine for you. That’s that’s a no, by the way, not a year, people.

[01:18:01] So this statute and one of the companion statutes actually has a provision for fee shifting. So if you’re a plaintiff and you win even one dollar in your civil rights lawsuit, like, let’s say you were stopped by the police, but you don’t actually have any damages. Right. Normally in tort law, there’s a lot of cases that never go to court just because the damages aren’t worth it. So if you get in a fender bender. Right, but the damage to your car is only like five bucks. Know, you’re not going to sue the guy who hit you over five dollars of damage to your car because it’s just not worth it. Right?

[01:18:39] In 1980, if you get it changes everything.

[01:18:42] If it changes that rule.

[01:18:45] And that’s the default rule for talks and changes at ninety three. If you have one dollar worth of damages or even if a jury decides you had no damages but your rights were violated.

[01:18:52] Right. You were stopped in an unlawful Terry stop for 30 seconds. You know, you can your attorneys will get paid for every hour they put into that case. And what this creates for cities is a huge issue where you can go to trial and win on almost every claim.

[01:19:13] But if you lose one claim and they’re entitled to one dollar, you’re paying out hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees. And this is actually what happened in Seattle with an office where I knew there he got a jury, found a one dollar verdict against him for violating someone’s civil rights. And the city had to pay out hundreds of thousands of dollars and attorney’s fees. So I think that the if you have a different system of civil rights litigation where you don’t get this fee shifting, you would, of course, still have lawsuits for things like uses of force that cause injury. Right. Because the monetary damages in those cases are going to be very high. But if you just totally get rid of qualified immunity with the system that we have now, I anticipate in New York City they actually added that there’s a thousand dollars automatic damages.

[01:20:13] So you know that the minimum damages are a thousand dollars for an unlawful detention or arrest.

[01:20:21] I was a plaintiff’s attorney in New York City right now, I would be like following the cops around and like every single person they stopped, I’d be giving them my business card. Right. Like and because that is going to be a gold mine for plaintiffs attorneys, the way that that is currently set up.

[01:20:38] The cops aren’t stopping anybody now. So, you know, it’s not quite true when it sort of is so. This reminds me or tells me how little I know about this even in my city of New York, but if it’s a if it’s how can a local city council change the law if it’s a constitutional standard?

[01:20:59] So they can’t.

[01:21:01] But what they can do and what they did, as I read the statute, is they’ve created a new cause of action in the city courts. And I don’t know enough about New York state or city law at all to talk with detail about this. But I know this has been done in several other states as well. What they’ve done is they create a new cause of action to allow you to sue the officers in state court for basically the same things you could have sued for in federal court under the nineteen eighty three statute. Like the law itself is sort of a clone of the nineteen eighty three statute just at the state level. And then they just add something to it that says and there’s no qualified immunity for this now. I don’t know how plaintiffs attorneys are going to use this in practice, they may not want to take these cases to state court for various reasons or strategic reasons.

[01:21:54] So I don’t know how that will actually play out.