The Stake-Out Squad

From 1968 to 1973, there is an interesting (to put it mildly) and surprisingly little-remembered part of NYPD history. The “Stake-Out Squad.” I’ve spoken to a few cops who remember its existence. One who was part of it. It’s impossible to imagine this unit existing today. And even back that it was controversial…. but very popular. Apparently other cities had the units as well. I don’t know which. [Update: Dallas]

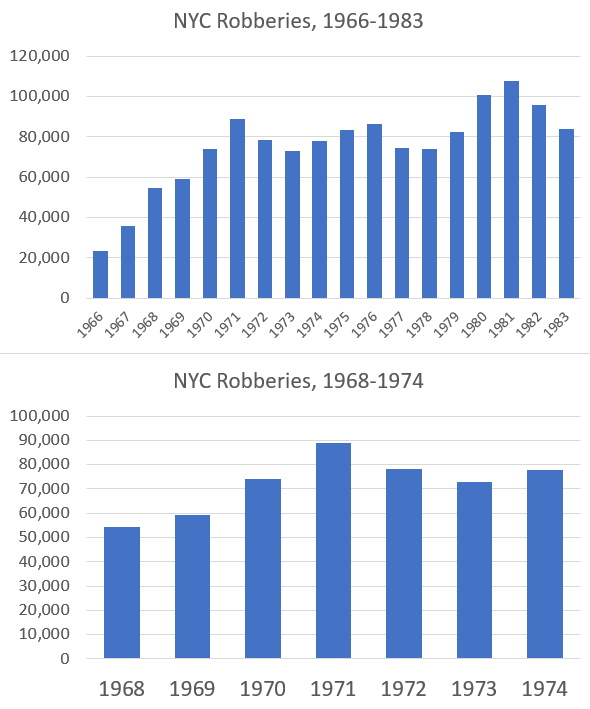

Still, if you want to know why police-involved shootings are down since 1970, this is one good reason. This unit shot 48 people (or maybe twice that), killing 24 (or more). All the victims were armed robbers, and this was a small fraction of the number of people shot by the New York City Police Department, but still…

The basic problem at the time was commercial armed robberies. There were more and more every year and somewhat out of control. The “progressive” “reform” police commissioner, Patrick V. Murphy gave a speech to the American Bar Association saying:

The court system must accept the giant share of the blame for the continual rise in crime. . . . We the police pour arrested criminals into the wide end of the criminal justice funnel, and they choke it up until they spill over the top. . . . Imagine each criminal as a rubber ball and the court system as a wall. We throw the ball against the wall and he bounces right back into the street again and commits another crime. The court system is not dealing with these criminals.

Sound familiar? The difference back then is a New York Times editorial applauded Murphy for this speech.

[The quote above (and below) are all taken from Robert Daley’s 1972 book, Target Blue, which I’m reading.]

The Stake-Out Unit put, say, two cops in liquor store during opening hours. And they’re wait, and watch, attentively, like hunters in a blind. They be in a back room behind a one-way mirror with a view of the clerk and cash register. The idea was since the same stores were getting robbed over and over again, you could just put cops in there and wait for the next robbery and confront the robbers. But then what?

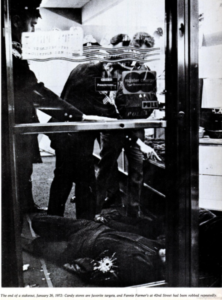

When the store was robbed, police would jump out at some time when the gun wasn’t at a worker’s head, and shout “Police. Don’t move, drop your gun.” Most of the time the gunmen would whirl to face the patrolmen.

“This is the classic pattern,” admitted Lieutenant James Brady, the commanding officer of the stake-out unit. “The guy turns with his gun pointed at us. If he does this, the guy is dead. My men are experts. If you run into my men, you don’t have a chance.”

There were general guidelines for stake-out work – the safety of innocent people was paramount – but no one went into a stake-out with the important answers. The definitive confrontation was new each time.

Each team each day was delivered in an unmarked police car, and once inside they were sequestered in the back room there; they had no latitude whatsoever until such time as they stepped forward to interrupt a robbery in progress. They could not move from that room.

From May 1968 to midwinter 1972, there were 212 requests by store owners through their local precincts for stake-out coverage. 182 of these were implemented. The results: 24 armed robbers killed, 19 wounded, 53 arrested.

That winter [1968-’69] alone, a total of seven robbers entered five staked-out stores. Six of them were killed and the seventh captured. There were two separate attempts to hold up the same store, Fannie Farmer’s on 42nd Street, next to Grand Central Station.

Two cops were shot in their vest and not-severely injured.

This hasn’t been a secret. There was a 1972 New York Magazine article, also written by Robert Daley, who along with writing Target Blue happened to be NYPD Deputy Commissioner of Public Affairs. And a goofy video re-enactment with bad actors, in which nobody gets shot. There was a book, Jim Cirillos Tales Of The Stakeout Squad.

In Daley’s Target Blue, Lieutenant Brady explained:

We do robbery work, and that’s all we do. There are 42,000 in-premises armed robberies a year. One out of every 2000 robbers bumps into us. I realize that we are controversial with all these killings, but we deal with a particular type of criminal. They come to us; no one goes out looking for them. No one pulls them in there. These people are not victims; they are the aggressor…. We have to get them; these are people who terrify, beat, pistol-whip store owners…. We capture as many as we can. If an armed man runs, even though maybe he plans to turn and shoot, my men have orders to lower their guns to shoot him in the upper leg or backside. We don’t shoot men with knives, or men who have already put their guns away, or who surrender.

My men all carry service revolvers of course, but their primary weapon usually is a shotgun, loaded with one-ounce slugs. If a gunman is hit with that, it is devastating. He’s completely disoriented.

We have never accidentally shot a bystander. It would be better if we didn’t have to shoot; but as soon as we step out, these gunmen normally point their guns right at us and so we must shoot. We don’t have the luxury of waiting to see whether they intend to shoot at us or not. It’s a problem.

No one gets killed because he stole money from a cash register, but because he menaced one or more innocent persons with a deadly weapon and the next time – or even this time – he may kill a shopkeeper or a customer. He is a potential killer. I have surveyed the records of 13 of the most recent gunmen we have run into and found that they had previously been arrested a total of 142 times.

Daley again:

On the whole, the Stake-out Squad did not go into ghetto areas. One day a request came in from Captain William Bracey, commanding officer of Harlem’s 32nd Precinct. Lieutenant Brady refused the job, saying, “If we kill somebody there you might end up with a public disorder of some kind.” Captain Bracey, who was Black, insisted, saying, “We have good people in this precinct and they’re entitled to police protection too.”

They set up one stake-out in Harlem, but perhaps word got out of the street, and the store was never robbed.

All of the operations of the Stake-Out Squad took place in full view of innocent witnesses, often dozens of them. Each confrontation was over in a few seconds, but each was subject to terrific review. Hours and even days were spent documenting them. Lieutenant Brady, who had disarmed a number of criminal and psychotic individuals but never shot anyone, responded to the scene of each incident. Usually Sergeant Milo, who also had never shot anyone, did too. So did Chief Arthur Hill, commanding officer of the Special Operations Division, whose command included the Stake-Out Unit, and so did a dozen or so superior officers and detectives. A district attorney was always called in, and testimony from civilian witnesses was taken at great length. There had never been a charge of unnecessary force and/or unnecessary gun fire against any member of the Stake-Out Squad.

Keep in mind this was going on under “reform” police commissioner Patrick V. Murphy (who served from October 1970 to May 1973). Ain’t reform great? The unit survived the significant change in the use-of-force policy of August 1972, when the NYPD, under Murphy, introduced a new policy restricting the use of deadly force to situations involving the defense of life, which replaced the traditional “fleeing felon” rule (which probably led but at least contributed to a massive nationwide reduction in police killing people).

After Murphy left in 1973, Police Commissioner Donald F. Cawley disbanded the Stake-Out Unit. Said the NYT:

It had been criticized because of the large number of hold‐up men it killed and because so many of them were black. Nevertheless, the squad, which made about four arrests for every holdup man slain, was highly popular among storekeepers in high‐crime areas, where it had more requests for stake‐outs than it could fill.

Let’s just go over those stats again. ~5 years. ~40 men. 182 stake outs. 24 armed robbers killed, 19 wounded, 53 arrested; 96 robbers were shot or arrested. For what it’s worth, in this video from the late 1980s, Jim Cirillo says 43 were killed and they arrested around four times that many alive. I don’t know which figure is correct, 23 and 43? And in a way it doesn’t matter which one it is. Less than half of the stake-outs (or maybe 3/4) resulted in a confrontation. Just under half the confrontations resulted in a robber being shot. And 5 to 9 robbers were killed a year, over five years. The results? Did commercial robberies go down?

I don’t know.

People I spoke to say yes. I actually do believe them. They tend to be right about these things I’ve found in interviewing a lot of retired cops and data I can check. But who knows? I can’t find the data. But city robberies overall did not go down. There were 54,400 robberies in 1968 and NYC didn’t see fewer until 1996. Doesn’t seem like the stake-out squad made much a dent at all. Who knows? There were 14,000 reported robberies in 2021. In recent years NYPD shoots and kills generally between 8 and 12 people a year. In 1970 police shot and killed 50 people; 93 in 1971; and 66 in 1972. It was a different time.